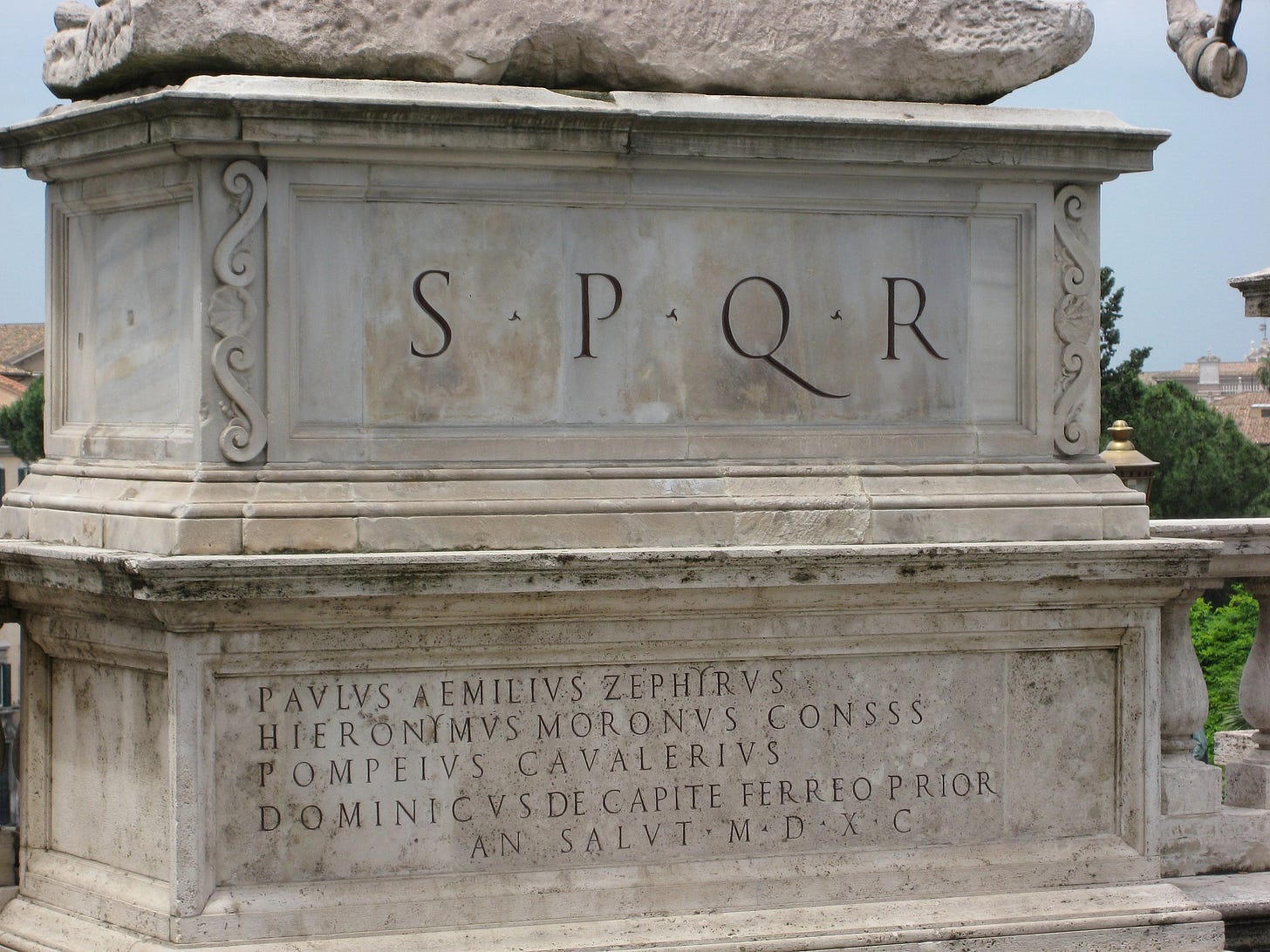

Atop the standards borne by Roman legions into battle were the four letters that, like the tetragrammaton, announced the ontology of the state, in all its glory and paradoxical mystery. SPQR. Senatus Populusque Romanus. I am that which I am. The Senate and the People of Rome.

So too was the phrase recorded in legal documents and inscribed on dedications to monuments and public works.

The Senate and the People of Rome. Two governing bodies. Two political entities that made up the ancient state.

The distinction between them was originally one of strict class division. The aristocracy and the masses. The patrician and the pleb. Although neither group was sovereign during the period of the Roman Kingdom, but bestowed the right of imperium upon the king and were his advisors, symbolically ratifying his decrees and sanctioning his actions. But with the exile of Tarquin and the rise of the Republic, the Senate and the People became the sole arbiters and protectors of their own rights.

The story of the Republic is the story of the relationship between these entities, the Senate and the People of Rome, and how the men who wielded them, whether patrician or plebeian, established the authority and defined the character of each.

Often it was the plebs advocating for enfranchisement and self-determination through the apparatus of the People, while the patrician men of the Senate asserted their right to rule by lineage and tradition, even as the social distinction between the classes become blurred through the intermarriage of families and the rise of the novus homo, or “new citizen.”

Still, the distinction remained an ideological one. To be part of a noble family and advocate for agricultural reforms or land redistribution on behalf of commoners was seen as subversive, a betrayal of norms, and most likely political posturing. To be a pleb, too, and rise through the ranks to become a senator or consul might give one a chip on one’s shoulder, or it might endear them to the system that allowed for their success.

Thus one’s political allegiance to either the Senate or the People of Rome could be seen as an endorsement for one of two kinds of governance. The former for a continuation of tradition and the maintaining of the mos maiorum, the latter for change and reform, a new way of doing things.

Either side could claim to be acting in the interests of the majority of Romans, for the good of the Republic as opposed to the narrow interests of their class or themselves.

In his Pro Sestius, Cicero posits that the only distinction is between those who serve and sacrifice for their country and those who seek to undermine and take advantage of it.

All those who defend these principles to the best of their power are "Aristocrats," to whatever Order they belong.

Whoever puts the interests of Rome before themselves he calls an optimate, or “best man,” a term which originally referred only to those of noble birth. Here Cicero says that anyone who is virtuous and seeks distinction among his peers is an optimate.

You, young Romans, who are nobles by birth, I will rouse to imitate the example of your ancestors; and you who can win nobility by your talents and virtue, I will exhort to follow that career in which many "new men" have covered themselves with honour and glory. Believe me, the only way to esteem, to distinction, and to honour, is to deserve the praise and affection of patriots who are wise and of a good natural disposition and to understand the organisation of the State most wisely established by our ancestors.

Of course Cicero’s conception of an optimate is a thoroughly conservative one. For him, the best are those who maintain tradition and follow the ways established by one’s ancestors. But that he makes clear this has nothing to do with one’s “breeding,” that anyone from any class is capable of gaining prestige and status in the Republic, seems a rather egalitarian sentiment. Whether or not he actually believed this (he’s giving a speech, after all) seems unimportant, because he expresses an idea which nonetheless might be taken to be true.

Indeed, men arrived on the scene and made names for themselves regardless of their breeding or upbringing (including Cicero himself, whose family was unknown). It was the aspirational nature the Republic engendered in its citizens that was the source of all of its success as well as the tragic flaw that would lead to its undoing.

SPQR I The two of us who raised our home, two free and sovereign bodies we, not kings but from our will alone come all our rights and liberty, the Senate and the People of Rome. II The consul in his purple toga flanked by lictors holding fasces strolls along the Via Sacra, full of handshakes as he passes. He goes to dictate from the rostra. III The tribune of the plebs convenes the motley tribes for an Assembly. He reads the case, and what it means. His duty is to keep them free. He makes appeals and intercedes. IV The Senate and the People know that glories in high office await. And any man, says Cicero, who sacrifices for his state, wins honor more than deeds bestow. V Whoever defends the commonwealth, whose aim is peace with dignity, who puts the public before himself will earn his own nobility, and the esteem of peers above all else. VI But one side is untrustworthy. One side refuses to play fair but uses lies and bribery, and of their schemes we must beware. With them there is no loyalty. VII Like hungry foxes in the pen inciting violence and sedition, traitors in the garbs of statesmen, they act but for their own ambition. Wicked, pernicious citizens. VIII We must not ever let them win for they would plunder all that’s good and cast the city into ruin. If not for us they surely would subdue, enslave, our kith and kin.

eerie and unnerving to see the word 'fasces' in a poem