There have always been two classes of men in this State who have sought to engage in public affairs and to distinguish themselves in them. Of these two classes, one aimed at being, by repute and in reality, "Friends of the People" [populares], the other "Aristocrats" [optimates]. Those who wished everything they did and said to be agreeable to the masses were reckoned as ''Friends of the People," but those who acted so as to win by their policy the approval of all the best citizens were reckoned as "Aristocrats."

—Cicero, Pro Sestio

In Rome there were two categories of citizens which politicians often made appeals to and allied themselves with.

The term optimates meant “the best ones.” Another word used was boni, “good men.” In contrast to the optimates were the populares, which, outside the realm of political rhetoric, meant simply “countrymen” or “fellow citizens,” but could also refer to “the people” or “the masses.” This is how Cicero distinguishes them in his Pro Sestio.

It’s important first to note that these were not formally established classes in the same way that the equites or the proletarii were social classes which could be defined by the property they owned or rights they held.

The optimates and the populares were rhetorical concepts, and they were employed by Cicero in much the same way that politicians today make use of the term “elites” or “the working class.” These terms signal allegiance to a psychological identity more so than the proximate material conditions that might be used to characterize them, such as class, birth, or wealth. A rich Democrat, for example, with a privileged upbringing and a lengthy pedigree, might declare themselves to be “for the working class,” while not being a member of that group in any real sense. Likewise, Julius Caesar, whose family name could trace its noble lineage back to the founder of Rome and the goddess Venus, claimed to champion the cause of the populares. One could profess allegiance for political advantage regardless of any actual affiliation.

Interestingly, in a democracy like America, while it’s clearly more advantageous for politicians to declare themselves to be for the populares, in the Roman Republic it was looked down upon, or at least regarded with suspicion, to do so. Thus, when Caesar, acting as consul, introduced bills for land reforms, he declared that he was siding with the people “against his will.”

The best and most honourable of the senators opposed it, upon which, as he had long wished for nothing more than for such a colourable pretext, he loudly protested how much it was against his will to be driven to seek support from the people, and how the senate’s insulting and harsh conduct left no other course possible for him than to devote himself henceforth to the popular cause and interest.

—Plutarch, Lives (trans Dryden)

Likewise, for Cicero, a politician who appealed to the populares usually did so because he was up to no good. Unable to win the favor of the “best ones,” the most upright citizens, he instead sought the support of the masses, which included all those unsavory figures: scoundrels, criminals, and profiteers, whose aim was not the prosperity of the State but their own selfish gain. This is in fact how Cicero distinguishes between optimates and populares, not by social class, but by a certain mindset which has the best intentions of the State in mind.

"Who then are these 'Best Citizens' of yours?" In number, if you ask me, they are infinite; for otherwise we could not exist. They include those who direct the policy of the State, with those who follow their lead. They include those very large classes to whom the Senate is open ; they include Romans living in municipal towns and in country districts ; they include men of business ; freedmen also are among the "Aristocrats." In its numbers, I repeat, this class is spread far and wide and is variously composed. But, to prevent misunderstanding, the whole class can be summed-up and defined in a few words. All are "Aristocrats" who are neither criminal nor vicious in disposition, nor frantic, nor harassed by troubles in their households.

—Cicero, Pro Sestio

The distinction here is a moral one, which is what the terms, and a profession of allegiance to them, are really meant to express. They are meant to indicate that we are on the side of the good and oppose the bad. And although in a democracy the goodness and badness of the groups is inverted, their principle rhetorical use remains the same. To be for “the working class” or “the people” is to be for those good citizens whose hard work and virtuous character ensures the proper functioning of the State, whereas to be for “elites” (as if any politician would openly express such a thing!) means to be for a parasitical class whose unearned privilege and narrow self-interest are a detriment to the greater good.

So much, then, for their political use.

Yet for the writer these terms are of use despite their misappropriation by politicians for their rhetorical ends. They do, in truth, represent two distinct groups of the social psyche. And they are as real to us now as they were to the Romans, to Cicero and to Caesar.

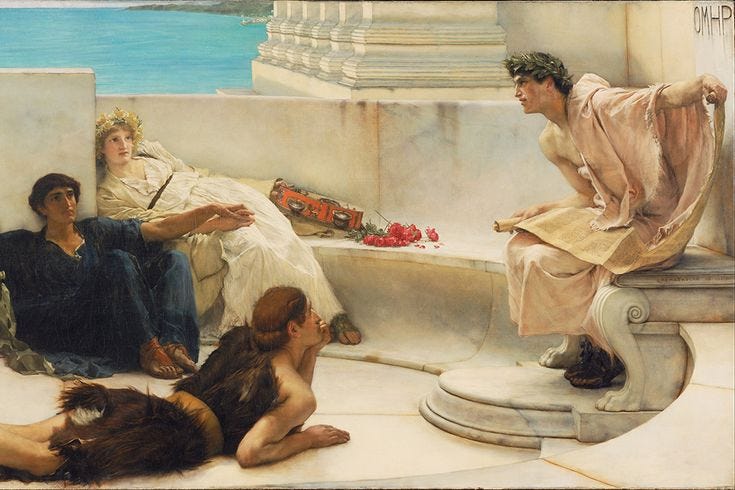

It’s their characters I’ve tried to sketch in the following poem, which is a sort of choral song, with strophe and antistrophe, of those archetypal forces that constitute the State.

Civitas The Optimates We are the best of men, the ones most fit to rule. They are the rest of them whom often we must rescue. We lead them by example because we are the best. They cannot help themselves but to be oppressed. The Populares We are the rest of men just trying to get by. Children of the innocent who toil and love and die. They tell us how things are, and how they want them done. We tell them go away, we’re fine. Here is no glory to be won. The Optimates They know not what they say, nor can they think like us. Or else they’d find a better way than toiling in the dust. They must be led, and those who can’t must step aside. The slow will never beat the quick. The blind must never guide. The Populares Yes they make things better, but do not make them good. They write the law to the letter, and break it when they would. They think they are above all but none surpass the gods. And when they push us too far they summon vengeful mobs.