The Landscape

Book One: The War in the Sink

Ch 1: Orus the Redwood

Ch 2: Oannes the Pacific Yew

Ch 3: Bostick the Valley Oak

Ch 4: Orchard the Canyon Live Oak

Stones have been known to move and trees to speak.

—Macbeth

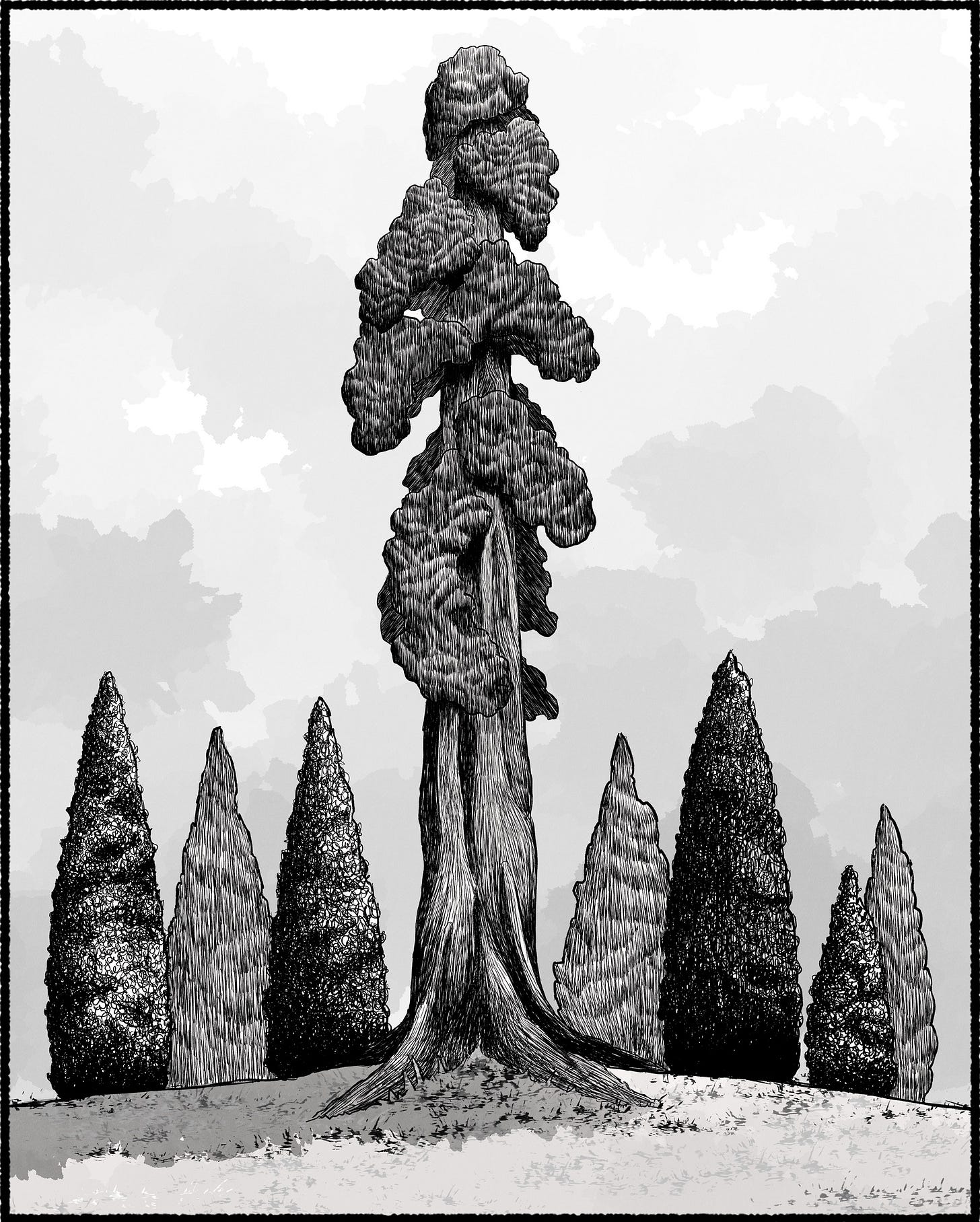

Now Orus having spent his days so long on the banks of the Sink, away from home, wending his shade through the fine tracery of mycelia that threads the banks together, returns to his treeself in winter and finds it forgotten, abandoned, fallen into disrepair, just as Oannes the yew had warned him. Fix the foundations of thy woody home, the old tree had told him. But Orus, eager for water for his grove, had not done so. Now beetles swarmed his wood and multiplied. Without pitch to push them out they burrowed deep in the fibrous bark and feasted within on the meaty cambium. Nor had he made to embitter his leaves tannins to keep the elk from nibbling his slender crown. His bark, young and smooth, was coming off in flakes, and his needles turned a pale, reddish brown. “What a mess I’ve made,” said Orus unhappily. “I’ve been so busy I haven’t made time to tend to those things that make me a tree. My habit, so long unattended, for I was out and about, appears so oddly foreign to me!” So he spent the cold months minding his home, and grabbed what dim light fell in splinters upon the frosty, dew-soaked floor, running the tips of his green fingers through silk strands of the Great Sun’s light the same as we stretch and articulate our own human hands to feel the gift of liveliness and of life. And he oversaw, too, the work of days, the household chores that make one’s place feel lived in, that make one feel like home. It is a tending to, a taking stock of, refilling this, replacing that. Restoring what’s been forgotten, all that’s diminished. How the upkeep like sweet nourishment revitalizes the weary body and the spirit! He measured with considered attention the opposing flow of xylem and phloem. The pores of his greens opening and closing, calibrating his panels of green scales, adjusting what had been knocked off balance. Venting water, circulating the balm air. He worked on himself long into every day, and paid mind to his problems with care, inquiring into himself what bothered him, wondering if the evil that plants do is what they truly intend to. “Or are they,” he thought, “under the wrong impression about what’s good?” The question vexed him. But at night, when plants settled down to rest, he put away his work and thoughts and stopped to listen to the songs of Ohmer the Pacific Bay. Now Ohmer the Bay loved telling stories. Her habit deeply-rooted, her trunk stout, her globed crown of yellow greens spinning, her roots thrumming with fantastical song. Plants would listen to her after sundown, long, long after their leaves had gone to sleep. And her fragrant crown, with aroma of pepper so lovely to smell, brought even the fauna around to listen to tales she had to tell. Orus’s favorites, and those most often told, were of the Last True Mother Tree of the Hill. Oasis he was called, a redwood braided together of six redwood trunks. A tree among trees who once stood near the stand where Orus stood, who, once upon a time, joined plants from all corners of the land. Ohmer told the story of how Oasis became braided of six redwoods like this: “Sing, Soil! Sing of giants past. Sing voices out of the earth, out of the richness of humus, of the force that drives the green fuse, of plants growing green and tall. Sing of the age of the tallest trees who lifted the Sky on their backs, who washed their heads in the stars. Remember Oasis, he whose six trunks were knotted into one. Oasis renowned for the marriage of Middle Hill, Oasis who brought flora and fauna together in harmony under one wood. How was it his habit was knotted? How did his trunks rise tall out of the life-giving humus like a corkscrew, gyring as they grew, churning the weather itself, stirring the heavenly cumulus season in and season out into their imaginary shapes? Was it not Djed the Javelin Oasis wrapped himself around? Djed the Giant, the Dread Monolith. Tallest of trees, the father of Oasis. Djed who was cast by the Green Spirit skyward, hurled like a javelin to pierce the Sun and unyoke its brightest light? And though Sylvia’s aim was true, not even She could reach the flaming eye. And down Djed fell, wounding Earth as it landed, straight as an arrow, into Middle Hill. And that is why they say the Hill has two tops, one side higher than the other. That table where Djed landed we call the Terrace, and the mountaintop we call the Summit. And after 10,000 years the Mighty Pine hardened into a lifeless snag and died. Unbent in the wind, Djed stood petrified. Its pale thread dissolving the separation of Earth and Sky, threatened the woods beneath its horrible shade, for they knew one day Djed would fall. Its brittle roots would give way. Its terrible weight would crash upon the floor and sunder all plantlife. So every day the shadow of Djed passed like a fateful sundial across the canopy. In that age of uncertainty plants lost heart. Trees trembled to feel their hour come, full of fear, obsessing over where and when the blow would be done. They lamented their pitiful state, cursed the Green Spirit for their existence. They mourned themselves while still alive and, enthralled to fate, ceased to thrive. But Djed did not fall. Plants in that grove were spared a terrible fate. How was it so? Around Djed’s buttressed feet, encircling its stupendous bole, a fairy ring of six saplings, six redwoods newly grown, sprouted from the knucklebones of Djed’s dying roots, arose fast as fungi’s fruiting bodies. Up they grew, fast and straight, each new torso quicker than the last, with arms springy and upward angled ready to embrace the Lightgiving Sun. And they were six voices in their trunks but were of one mind, and spoke with one voice out of the ground. And he together who spoke as all six was called Oasis. A council of redwoods. Six of them in the round. A fairy ring. And when Oasis was a treeling he reached out his roots around him and learned how plants both short and tall feared the day when Djed the Snag would fall. How they trembled in the shadow of Djed pirouetting its dreadful hand across them. How it reminded them daily of their end! Oasis heard their complaints, and said: ‘Oh goodly plants, be not afeard of Djed. The snag is only now our burden. Only now, this very moment, the still point of a turning world. But it shall be there, at the center, my dance begins. I will perform the sacred choreography of a son doing the impossible for his parent, to keep their image from crashing from whatever height and causing unforetold catastrophe. I am the tree whose habit will be the thinking on it as long as I grow. And when I am a hundred feet tall I will have made myself a wall around my father’s ruinous abode. And out of a desolate place I will have made a more perfect space than even the Great Glade knows.’’ At this some plants gasped and clamored: ‘No place is greater than the Great Glade!’ Many others believed anyway such a thing was impossible. It simply could not be done. Pines don’t grow like that, they said. You’re no willow or oak or witch hazel. But he would prove them wrong. Leaning his bodies clockwise he corkscrewed around the Mighty Snag, with tilting trunks, with crowns outstretched from their butts, twisting like a vine, coiling like the tendrils of a sucker until the six trunks were intertwined, and the trunk of Djed entombed. Fifty and a hundred summers he weaved his selves around the menacing pine. Fifty and a hundred summers plants watched with incredulity and suspicion, with hope and curiosity and expectation, and every bearing they brought was delivered unto its opposite or concomitant, turning on the very gyring of his trunks. They watched his slanting bodies cross and recross, the fibrous bark scraping and squeezing against bark, threading themselves the thickness of their boles, until, bound tightly together, he closed their helixed habits around the Mighty Djed and held it in place, safe from windthrow or fire, though the monstrous pine was dead. Word spread throughout the roots, and legend grew of the redwood’s woven habit, how he saved his stand from certain disaster, becoming a plant upon which other plants could depend. And that is how Oasis the redwood was braided of six trunks into one.” Thus ended Ohmer the Bay’s tale that night. Plants around her loved to hear her songs and listened long after their leaves had gone to sleep, until dawn brought the morning fog and the first corpuscular rays shimmered wetly through the mist, and their work began. But there was one tree who did not enjoy Ohmer’s stories. One tree who listened unmoved except to bitterness. Not long after the bay’s song had ended, that tree’s voice called out from the roots to object. “Oh bard, will you vex them yet again, and keep them in thrall to delusion? These dreams you tell, these fictions, are they not cut from whole cloth? Do you not, being a laurel, pepper them with fragrant airs and perfumed pomp? They go down most sweetly to our roots, filling us up, making us overfull and sleepy. And ere they’ve sent us off to dreaming, stupefied, spellbound and unquestioning, the first light breaks, and it’s back to work.” The tree spoke sharply from his plot, his voice traveling down a nurse log not far from Orus. The two trees could sense one another through their lens of greens, and taste of the other with the porous nostrils of their leaves. On one side of a ravine Orus stood, on a landing of shaggy boulders flanked by heaps of ferns and bearded moss. Around his feet were fleshy worts and springy sorrel. At forty feet, he was still a young redwood whose slender trunk swayed to stay upright, whose new sprays of greens did not yet veil the light of the floor but made it bright, a lamp within the shadowed forest, a vigil illuminating with vivid yellowgreens. But below the landing, a gully and a stream, and at the toe-slope where the stream pooled, beneath a pile of woody debris, there lay a sodden nurse log upon which the colonettes of a western hemlock grew. Four trunks in all arose, shortest to tallest in a row, like the fins of a sailfish. And the bare roots that ran down either side of the nurse log looked like the legs of a man mid stride, knees bending midhike against some precipitous incline. To see his habit running lengthwise, the tangled roots, trunks, and crowns, all seemed as though in stages of climbing or standing up or ascending a staircase of some dark cellar that led down to the depths of the Earth. Each tree trunk looked as phases in a sequence of hatching from the shell of the fallen log, splitting open, emerging primordially from the rank decay of that primeval bog. And the fourth and final tree reached forward from the bow of the log, his hands and the tip of his drooping head extending upwards where light fell more bright and generous near the landing where Orus stood. “Oh bard, I applaud you, being masterful, but what a shame it is, what a crime that talent such as yours goes to waste. You wield it in the service of taller trees, to fertilize and enrich their hierarchy, which cares not for you for your own sake but for the value of the product you make, for it keeps plants dumb and domicile.” Having heard the hemlock make his remark many times already, Orus felt it had been one time too many, and replied: “Hammett, this is not the first I’ve heard of your complaint against Ohmer the Bay. But I’ve always wondered whether or not you believe in what it is you say. Do you believe Ohmer sings her song merely to deceive us, to do us a disservice and serve the benefit of unsavory trees? And if you do believe it, will you not then give us proof of such a thing, or else these accusations seem unjust to Ohmer. I think she moves many plants, including me, for our own good with her beautiful song.” And Hammett said: “How is it possible for a treeling to rise this tall and still be so naïve! You have a lot to learn, redwood, about how the Watershed really works. I say the bay does her work unwittingly. It’s mechanical. Nothing malevolent. Just ignorance and weakness. I’m sure she’s just as naïve and incapable as you. She sings heroic songs of the good and brave and we think that is how one must behave if one wants to rise high in the canopy. But of course this isn’t the case. The tree who grows tallest does so because he’s willing to do whatever it takes, including wicked things, to secure his place and win a spot in the Sun. But the bay doesn’t tell you stories like this. Instead she sings about benevolent Oasis. Do you think Oasis was benevolent as she says? If you do then you’re beyond my help, keehl, and beyond deserving any sympathy from me. The bay lies about the braided tree’s true nature, and in so doing, puts you at a disadvantage, because the tallest will use that good that you believe against you to achieve their own ends. Whether the bay knows she lies or not, whether out of ignorance or malevolence, it makes no difference. She is still to blame for making plants believe her silly stories, and for that, at least, she should feel shame.” Now day broke. The Sun with provident yoke spilling over the horizon summoned plants to their bright and early morning feast, and Hammett returned to his treeself. But Orus lingered a little in the rootal networks, remarking on the opinions of the hemlock. “The Sun knows how a tree gets to be like that. His talk so bitter, his opinion impenetrable. Not even Oannes the Teacher could see into that hardened cylinder of heartwood.” But Ohmer the Bay, the Laurel of Song, replied, “Hammett has his reasons, redwood. He is descended from an accursed line of hemlocks. The Children of Hammett. Doomed to a lifetime of ceaseless wandering. Doomed for that crime committed by his ancestor, Hammett the Elder. Hammett the Pine Who Grew Crooked From The Scree. Much does our younger Hammett have to weigh and bear in the recesses of his pith. It was Hammett the Elder, his forebear, who overthrew the Last True Mother Tree of Middle Hill, the Great Braided Oasis.”

This story is so engaging. The trees like us humans have been given different attributes like virtue, selfishness and it is through this moral tapestry that their dialogue, conversation and character unfolds

“Around Djed’s buttressed feet,

encircling its stupendous bole,

a fairy ring of six saplings,

six redwoods newly grown,

sprouted from the knucklebones

of Djed’s dying roots, arose

fast as fungi’s fruiting bodies.”

This stanza is sticking with me. I’ve re-read it so many times and want to come back and read it more. Obviously its context grants power but the image itself is gravitational and exquisite. Well done as always.