If it is true that man finds the proper abode of his existence in language—whether he is aware of it or not—then an experience we undergo with language will touch the innermost nexus of our existence.

—Heidegger, On The Way To Language

The Imagination as Activity and Place

In the last post we made some remarks about the nature of the imagination and poetry’s role in shaping it.

The imagination is a level of consciousness (we can also think of it as an ‘activity’ of consciousness) that mediates between the psychical realm of experience, the realm of pure sensation, and the intellect, or the thing that concerns itself with concepts and relationships between them. This activity happens ‘blindly,’ Kant says, in the sense that it is always active, without our awareness or our thinking about it. Or we can think of it, as R.G. Collingwood does in The Principles of Art, as being blind in the sense that it “cannot anticipate its own results by conceiving them as purposes in advance of executing them.” The imagination, in other words, is autonomous, and not subject to the aims of the will. (Coleridge makes a similar point when he distinguishes between the imagination and fancy.)

But we can, with effort, ‘turn our attention’ to the objects of imagination. We can raise our awareness such that they become objects of our attention. And when we do this, we’re said to be in possession of them. We become conscious of them as belonging to us, and we enter into an imaginative experience.

Consider, for example, the following scenarios. You’ve had a sour interaction with a coworker, or someone you’re romantically interested in has offered a subtle invitation to you in some way.

The interaction incites a feeling. Primitive and nebulous at first, the feeling lingers as a feeling, until it draws your attention. Then it becomes an experience of the imagination. It takes the shape of your thinking. What exactly is it that I feel toward that person? It might be quite easy to articulate this to yourself, or it may take time to coalesce.

I did not like the tone of voice my coworker used.

She might like me, too.

The experience clarifies itself in your mind as the impressions, vague at first, are formed and made coherent according to your understanding.

The way my coworker makes demands of me is unacceptable to the standards of my job, as I see it.

There must be something there between us that we both feel, and she’s noticed it as I have.

You attend to the feeling such that it forms the outline of a clear idea.

What I feel is subjugation and injustice at the hands of someone who is not my superior, but who pretends to be.

I will say something to her, and see where this goes.

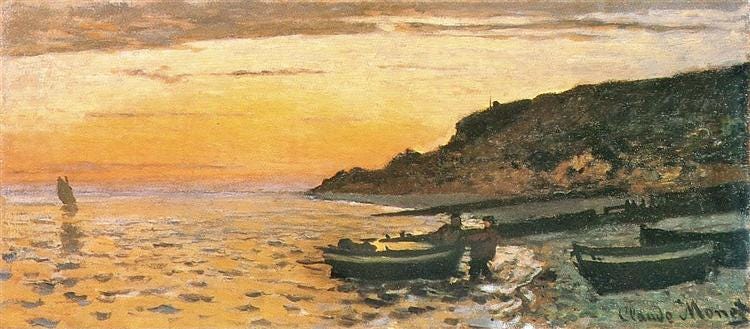

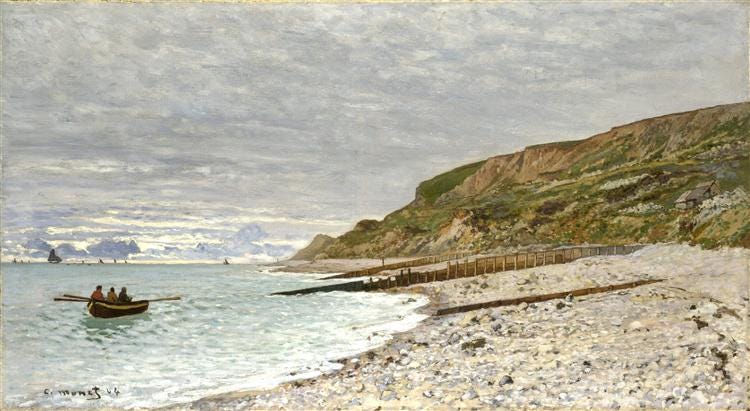

Here’s a more difficult example: you’re walking with your friend along the boardwalk at dusk. You decide to go down to the shore. The ocean is beside you, and as you walk you notice a woman in the distance, singing. You and your friend are struck by her singing, and by the sea, and as you return to the boardwalk, you feel yourselves changed by the experience in such a way that the lights of the city, and the lights of the fishing boats, have taken on new meaning. The experience is clearly profound, yet equally as difficult to make sense of. Indeed, it seems impossible that such a thing could ever be fully understood. The feeling is too uncanny. It transcends all understanding. The idea that it could be made to fit into anything seems antithetical to the experience itself, so changed have you become that the very concepts by which you made sense of the world themselves have been transformed.

Still, the imagination is the only means by which we can really approach such an experience. It’s there, at least, in the imagination, that the possibility of giving shape to such an experience exists, for it’s there that language, in its true nature, clarifies our relationship to Being.

What is Language?

Heidegger called language “the house of Being.” In his lectures On the Way to Language he says language is the place where we come face-to-face with the possibility of an experience with Being. To unpack such a loaded phrase, we first need to understand what we do not mean when we talk about language.

In a previous post, we spoke about the characteristic use of language as more closely related to thinking than speaking. Chomsky observed that language, at its core, is better suited to the internal operations of the mind than to external communication. Although certainly language has adapted itself for such communication, and quite successfully, too. But this kind of language is more similar to other modes of communication, like the printing press or the internet. It’s language for the purposes of reproduction and dissemination. It’s a product of the actual activity of language, but not language as such.

What, then, do we mean when we talk about the true nature of language?

In his lectures, Heidegger turns to the ethnolinguist Wilhelm von Humboldt, whose work he considers foundational for all subsequent philology and philosophy of language. In the introduction to his work on the Kavi language of Java, published separately as a treatise after his death by his brother, Alexander, von Humboldt characterizes language in the following way:

Properly conceived of, language is something persistent and in every instant transitory. Even its maintenance by writing is only an incomplete, mummified preservation, necessary if one is again to render perceptible the living speech concerned. In itself language is not work (ergon) but an activity (energeia). Its true definition may therefore only be genetic. It is after all the continual intellectual effort to make the articulated sound capable of expressing thought. In a rigorous sense, this is the definition of speech in each given case. Essentially, however, only the totality of this speaking can be regarded as language.

—“On the Diversity of the Structure of Human Language and its Influence on the Intellectual Development of Mankind”

Here again we find language’s relationship to thinking. Collingwood echoes this sentiment a hundred years later.

In one sense language is wholly an activity of thought, and thought is all it can ever express; for the level of experience to which it belongs is that of awareness or consciousness or imagination, and this level has been shown to belong not to the realm of sensation or psychical experience, but to the realm of thought.

—The Principles of Art

Language comes into being at the level of thinking. Thinking is the place of its activity (energeia). And it is a place for Heidegger. He speaks of reflective thinking as a country.

Speaking allusively, the country, that which counters, is the clearing that gives free rein, where all that is cleared and freed, and all that conceals itself, together attain the open freedom. The freeing and sheltering character of this region lies in this way-making movement, which yields those ways that belong to the region.

—On The Way to Language

It’s in this region that we come to understand Being through our encounter with language. Language clarifies to us what it is that’s there. A feeling of resentment toward a coworker. A burgeoning romantic relationship. An encounter with the ineffable by the sea. It is the totality of experience that arises in the imagination when we become conscious of ourselves in the world, as well as the means by which we express that experience to ourselves. And that ‘becoming conscious’ is precisely the activity of language, for language is what gives shape to those experiences that would otherwise remain formless and murky at the level of pure sensation. Without language we cannot ‘see’ the country, we cannot perceive what’s there, and cannot be conscious of ourselves as grasping and belonging to it. Without language we are like all those organisms that we say exist but are not conscious of their existence, all those animals and plants we think of as merely responding to sense stimuli.

The Necessity of Poetic Language

But every experience, every encounter with Being, is a new and previously unencountered one. It is composed of the material sensations and formal emotions and concepts which are never experienced in quite the same way. This is the second part of von Humboldt’s observation that language is “something persistent and in every instant transitory.” The language that we use, even when we use the same language, takes on new meaning in the context of new experience. This is why language is not a work (ergon) but an activity (energeia), and why the language of speech is not the true nature of language. For while speech wants to settle meaning into something solid and communicable, the true nature of language is not to be fixed but readily adaptable to novel expression.

Collingwood observes this fact as well when he talks about the grammarian and the lexicographer’s use of language.

Language as it lives and grows no more consists of verbs, nouns, and so forth than animals as they live and grow consist of forehands, gammons, rump-steaks, and other joints. […] Language would not remain language unless it remained expressive; and it can do this only by resisting the grammarian’s efforts so far as to retain a measure of its original vitality.

So we come to the work of poetry, which strives continually to refresh language with new figures for the imagination, to cast new shapes, that we may be constantly renewed in our experience with Being.

Heidegger realized this. He makes much of the poet’s relationship with language in his lectures. In the country of thinking, he says, thinking and poetry share a nearness, a neighborhood.

Poetry and thinking are modes of saying. The nearness that brings poetry and thinking together into neighborhood we call Saying. Here, we assume, is the essential nature of language. “To say,” related to the Old Norse ‘saga,’ means to show: to make appear, set free, that is, to offer and extend what we call World, lighting and concealing it.

Poetry is that art which “sustains and shapes imagery using no other means than language” (Ricoeur). Poetry figures the imagination with language, and by that figuring we’re shown a vision of the world that clarifies and augments consciousness.

What does such a vision look like? Next time I’d like to investigate the vision that Wallace Stevens had on the beach at Key West, overhearing at a distance a woman singing. Stevens, not only the best poet of the 20th century, is also the supreme poet of the imagination. He writes about the realm of thinking itself, and thinking’s encounter with Being. His work restores vitality to words and refreshes the activity of language that make such encounters possible. It’s with him that we shall find ourselves more truly and more strange.

Finally, a word from Harold Bloom.

The art of reading poetry is an authentic training in the augmentation of consciousness, perhaps the most authentic of healthy modes.

Pale Ramon, to his patron, the rich insurance executive/poet who visits the Keys every September and pays good money to charter his boat for fishing trips: "It's because we split a bottle of rum, Senor Stevens. That's it. Nothing a cup of strong black coffee won't clear up."

look forward to the wallace stevens instalment!!