What, then, is time? As long as no one asks me, I know; but if someone asks me and I try to explain, I do not know.

—Augustine, Confessions XI.14.17

In Book XI of the Confessions, Augustine puzzles over the concept of time, and the distinction between past, present, and future. He considers how odd it is that there is such a thing as ‘long’ and ‘short’ time. How can something, he wonders, be ‘far’ in the past or ‘a long time off’ in the future if neither exists in the present? How can the past and the future possess qualities like ‘extension’ and ‘distance’ if they aren’t present? He further wonders if the past and the future had those qualities of longness and shortness in the present. Was there such a present that, when it was present, was longer or shorter than any other present?

In Metaphors We Live By George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argue that most of the fundamental concepts we have, like time, are organized and made sense of in terms of one or more spatialization metaphors. Time is, of course, money, but it is also ‘ahead’ or ‘behind’ us, and might be very near or far off in the distance. So, too, is it like a place we can make our way through, following along our paths or veering off course. We can live ‘in it,’ too, as a recent movie title suggests.1

Whether or not one takes these and other metaphors for granted in their writing seems, to me, a good way of characterizing the difference between the writer of prose and the writer of poetry. It’s in the approach to language that we see a fundamental difference in the poetic and the prosaic. The poet and the prose writer have different stances toward language, a different spirit in which words are taken up.

The writer who writes and uses the phrase “a long time ago” and feels no qualms as to its meaning, as Augustine did, I should call the prose writer. But the writer who attends to such metaphors, as a matter of the writing itself, I should call the poet.

It’s exactly this figuring the poet is concerned with. And not only with metaphor but the whole figurative grammar available to him. Figures of thought and figures of sound. Figures and patterns of all kinds in the imagination that language effects.

The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur once remarked that “the poet is that artisan who sustains and shapes imagery using no means other than language.”2

It is the poet’s duty to shape his imagination in such a way that consciousness reveals itself through, and is constantly refreshed by, his language. The act of figuring does this. The poet casts figures and revives others that have lain petrified. His language, not always new, is always revitalizing, always enlivening to the imagination.

Figuring Time

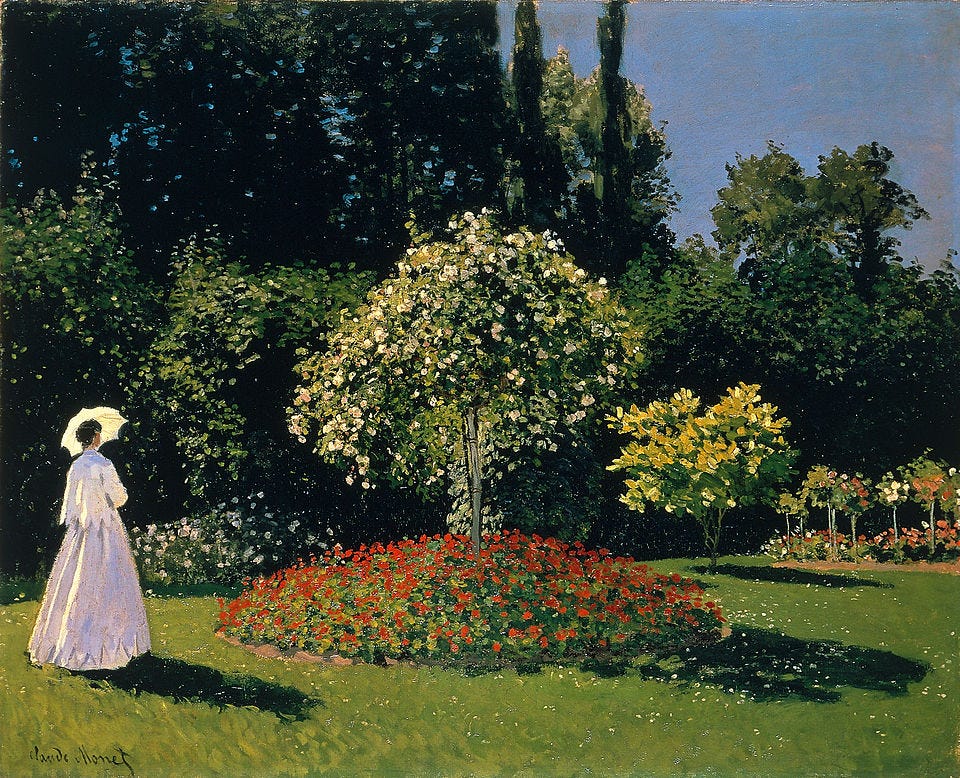

The poet may figure time by means of metaphor, and so imagine it as if it were a thing to draw near, or a place to inhabit. He may also figure time by means of sound, such that we not only conceptualize time, but experience it.

To accomplish the latter, the poet patterns their lines into rhythms. The pulse of the iamb, the jingle of the anapest, the sonority of the spondee. A uniformity in rhythm we call Meter, which is time made language. It is a temporal experience. To read verse aloud, one is conditioned to read according to the time of the poem. This is a different thing than reading prose. We follow the poem’s measure and tempo, which are in direct relation to time. It is a different thing than, say, the pacing of a prose writer, or the cadences one finds in prose. Surely both kinds of writing, poetry and prose, propel us forward through non-metrical means, by the grammar and narrative and the progression of thought. But meter puts us into a direct relationship with time, one in which we feel the ticking of the clock, and the movement of time, by means of measured beats.

You can approximate this experience yourself with a simple experiment using music. Pick a song whose lyrics are non-metrical. Read the lyrics on the page without listening to the song, and without listening to the song in your head as you read. Disconnect yourself as much as you can from the music of the song, and read the lyrics on the page as if there were no voice singing them in your head. Then play the song and listen to it.

The difference is striking. One is temporal, the other not at all. In song the words are given a temporal existence, while on the page they have none at all. This is something like the difference between reading prose and reading verse.

Meter the Music of Words

Meter is the way we give temporality to words by virtue of the words themselves. No musical instrument is necessary.3 Simply to read the line is to hear the rhythm, as in the following

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though

Here the regular occurrence of stress on every even syllable creates an iambic rhythm. In traditional English verse, rhythm is created through the patterning of stressed and unstressed syllables. The basic unit of measurement, the foot, contains two or three syllables, some stressed, some not. The names of different types of feet, the iamb, the trochee, the anapest, the dactyl, come to us from antiquity, from the Greeks, whose meter was based not on stress but on quantity, on the length of vowels and not the accent of syllables (more on this later).

The poet writing in verse conditions the reader to a rhythm such that, even when variation is introduced, an underlying rhythm persists. The reader’s senses are thus always attenuated to time. A good example of this is another poem by Robert Frost, “Birches”.

When I see birches bend to left and right

Across the lines of straighter darker trees,

I like to think some boy’s been swinging them.

But swinging doesn’t bend them down to stay

As ice-storms do. Often you must have seen them

Loaded with ice a sunny winter morning

After a rain. They click upon themselves

As the breeze rises, and turn many-colored

As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel.

Here an iambic rhythm is introduced in the first few lines, so that even when a change occurs (at “Often”) the reader still hears the poem according to the meter. They have been conditioned to read the poem in such a way that the regularity of the rhythm persists even when different feet are admitted, such as the dactyls “Often you,” “Loaded with,” “After a,” and “As the breeze.” But because Frost returns throughout the poem to that baseline rhythm—the iambic line we hear in the opening—the meter is always reinforced even when variety is introduced.

I admit I was once confused by the way that rhythm in a poem could continue even when the feet that made it up were replaced. I lay the blame partly on my tone deaf childhood. I was terrible at music. I couldn’t keep a beat to save my life, and I still have trouble distinguishing notes. I have whatever the opposite of perfect pitch is.4 So, when I was in high school, I could hear the lexical stress in words, but not always the rhythm of the lines my teachers would read aloud, unless they exaggerated the accent. “the WOODS are LOVEly DARK and DEEP / but I have PROmiSES to KEEP/ and MILES to GO beFORE i SLEEP.” But when their voices fell back into something like the normal cadence of speech, the sense of the rhythm would fade.5

Thus, when I scanned a poem, I imposed the meter upon it, in a top-down way. If it was iambic pentameter I marked every line with iambs, and tried to read it that way too. I remember Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29 giving me great difficulty at the time.

When, IN disGRACE with FORtune AND men’s EYES,

i ALL alONE beWEEP my OUTcast STATE,

And TROUble DEAF heavEN with MY bootLESS cries,

Anyone who reads it by imposing the meter upon it ends up with an awkward, mechanical mess. No doubt I thought Shakespeare was out of his mind to write in such a way. No doubt every time I came across a line that didn’t scan perfectly, I was thrown into confusion. Nor were my teachers much help. They could neither fix my musical deficiency nor explain the nuances of meter to me, for they knew little more than the names of feet, and which poems were supposed to be in which meter.6 They could give no good reason why, if the meter was merely its feet, how it could be said to persist when the feet varied. It was only later on that I realized this was because meter had more to do with time than with syllables. But with such a surface understanding as I and my teachers had, it was easy to be confounded by variety, which all good poems must possess.

Later on, in college, when we discussed meter, we would hyperfixate on scansion. The morass of scanning a line, of scrutinizing and pondering over the intention of an extra syllable, over whether or not this or that word should be stressed, made me start to think the whole practice of meter was a waste of time. It rarely added to the conversation, and often distracted us from it, because we talked only about the mechanics and often disagreed about the right way to scan a line. The poem itself seemed to get lost in the weeds in superfluous considerations. What did it matter anyway where the stress fell in a line if the rhythm worked? What interested me more was that it worked despite its variation. How could it do that? How was it working when we couldn’t agree on how exactly it worked in the first place?

Consider, for example, how it’s possible that the same meter can produce such vastly different lines in Paradise Lost as

Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit. (P.L., I. 1)

Say, Muse, their names then known, who first, who last. (ibid, I. 376)

Fled over Adria to the Hesperian fields. (ibid, I. 520)

Rocks, caves, lakes, fens, bogs, dens, and shades of death. (ibid, II. 621)

Strange horror seize thee, and pangs unfelt before. (ibid, II. 703)

Life in myself for ever, by thee I live. (ibid, II. 244)

And where the river of bliss through midst of heaven (ibid, III. 358)

Millions of spiritual creatures walk the earth. (ibid, IV. 677)

Burned after them to the bottomless pit (ibid, VI. 866)

Yet fell. Remember, and fear to transgress (ibid, VI. 913)

Because thou hast harkened to the voice of thy wife (ibid, X. 198)

In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread. (ibid, X. 205)

Me, me only, just object of his ire. (ibid, X. 936)

With dark and javelin, stones and sulphurous fire (ibid, XI. 658)

There’s so much variety in Milton’s work that to say it’s written in blank verse doesn’t say very much at all, either about Paradise Lost or about iambic pentameter. We get lost in the variety itself, and end up with no way of evaluating the lines according to their meter.7

The problem is that, in studying meter, we often lose sight of its true nature. Meter, again, is time made language. It is the figuring of time which brings the experience of it to our minds. Reading verse, one is made aware of time by the regularity and recurrence of the lines. We’re made conscious of time, and made conscious of the way in which it is a distinct and separate thing from the syllabic structure that calls it to mind.

What is Meter?

This juxtaposition, between time and syllable, is how we actually produce metrical effects, and how we generate variety in verse, as the 20th century Scottish literary critic T.S. Omond pointed out in A Study of Metre.

Isochronous periods form the units of metre. Syllabic variation gets its whole force from contrast with these, is conceivably only in relation to these. Forgetfulness of this fact leads to false theory and incorrect practice. Unless temporal uniformity underlies syllabic variety, verse ceases to be recognized as verse.8

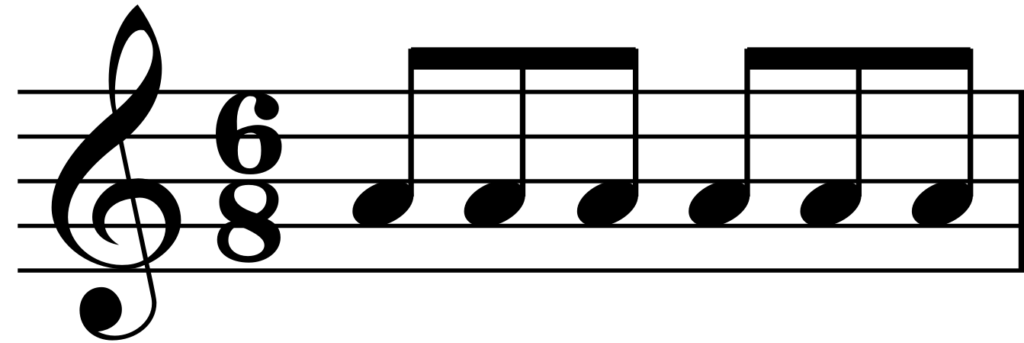

It’s not the syllables themselves that make the meter. Rather, it’s better to think of syllables as filling up the time a poem is set to. Poetic Meter, like a time signature in music, conditions us to certain periods of time and not necessarily to syllabic quantity or accent. Instead, syllables fill in the time (while accent roughly corresponds to beat). Once I understood this principle, I had a much easier time with verse, both reading it and writing it.

T.S. Omond (1846–1923) approached meter from the point of view of a grammarian. He was writing in opposition to the scholars and metrists of his time who relied too heavily on classical modes of meter inherited from the Greek and Latin. Their classical theories, he claimed, were often misapplied or outright false in regards to English verse. A Study of Metre (1903) was an attempt to investigate and develop a general theory of meter that accounted for the characteristics of English verse while shedding any superfluous vestures of antiquity.

Metrical effect depends on certain broad principles, simple in conception (for a child can enjoy verse), yet capable of endless elaboration and development at the hands of accomplished singers. In considering the latter aspect we have, perhaps, somewhat lost sight of the former. No building is secure without a good foundation. The most complex, and refined, and specialized theories of verse-structure stand or fall by compliance with certain plain, elementary, fundamental truths.9

Omond was after a description of practical principles of verse uncomplicated by schools of ornate and overwrought prosody. By his time such theorizing had gotten so out of hand that, as he cites in his book, one prominent critic had catalogued twelve hundred and ninety-six possible cadences, while another had categorized forty-five different degrees of syllable-prominence. No doubt such academic systemization played a role in the decline of meter altogether, as no poet writes according to such rules, and no reader references such handbooks to help them understand a poem. The classification of feet, the rules of elision, the “undue narrowness and artificiality” of definitions, muddles rather than elucidates rhythm, as anyone who’s ever bickered over how to properly scan a line can relate.

Indeed, the untutored reader as well as the expert will often be at a loss to say why a particular sequence of syllables should be classed as one “foot” rather than another. Such nebulousness of result is surely proof of failure in the working of any theory.10

Time the Measure Taken

I was familiar with such nebulous results from college, when we might spend half the class discussing what meter a poem was in, without ever getting to consider its value to the poem. It was experiences like these that first drew me to Omond’s work. In A Study of Metre he presents an alternative, practical theory for identifying and evaluating a poem in terms of its meter.

What Omond does is ground an understanding of poetic meter in something like the principles of modern music. He takes as the fundamental unit of meter not the foot but the period. Whereas a foot is determined by syllables, a period is a measure of an interval of time. That interval is occupied by syllables, and denoted by stress, but is distinct from both of these. The period is analogous to a musical bar.11 Syllable and stress, like notes of varying values, fill the bar and keep the time, while adding color and character through variation. But what underlies them always is the regularity of a certain recurring timespan.

The time-measure of each line is identical, but in one case it is less completely filled by syllables. This view presents no difficulty, when one has grasped the fact that time-spaces exist apart from the syllables embedded in them.12

In a bar of music the time signature indicates the number of beats per line, as well as the value of each note. It denotes an underlying ideal structure upon which variety is built, so that, while some notes may be longer or shorter than others, and some may not fall exactly on their beats, or may be absent altogether, yet a uniformity of rhythm is maintained.

So, too, is poetic meter like a time signature, in that it indicates something about the underlying rhythm to which the syllables of the line correspond. It tells us about the time to which the syllables should be “marshalled.”

Omond claims there are two basic times in English, Double and Triple Time.13 Their rhythm is either rising, as in iambic and anapestic meter, or falling, as in trochaic and dactylic meter. In this way Omond’s theory of periodicity isn’t all that different from how we traditionally scan a poem. The crucial difference, again, is the emphasis on time and not syllabic structure. This change in emphasis does much to clear up the confusion that arises when we scan poems, and allows us to evaluate variation not as an irregularity but as a feature of the poet’s style as it interacts with the meter.14

Judging Metrical Effect

A classical understanding of meter is useful for identifying those uncomplicated forms of verse, as in some lines from Andrew Marvell

And all the way, to guide their chime,

With falling oars they kept the time.

The structure is clearly iambic. Its rhythm is regular, its sound pleasant if perhaps a bit monotonous. But now consider the poem “The Higher Pantheism” by Tennyson, which begins

The sun, the moon, the stars, the seas, the hills

We might at first assume, like Marvell’s, that the poem is iambic. But the first line actually ends with the phrase “and the plains.”

The sun, the moon, the stars, the seas, the hills and the plains,-

What at first seems iambic turns out not to be. And yet there is a rhythm that underlies the whole poem.

The Higher Pantheism The sun, the moon, the stars, the seas, the hills and the plains,- Are not these, O Soul, the Vision of Him who reigns? Is not the Vision He, tho' He be not that which He seems? Dreams are true while they last, and do we not live in dreams? Earth, these solid stars, this weight of body and limb, Are they not sign and symbol of thy division from Him? Dark is the world to thee; thyself art the reason why, For is He not all but thou, that hast power to feel "I am I"? Glory about thee, without thee; and thou fulfillest thy doom, Making Him broken gleams and a stifled splendour and gloom. Speak to Him, thou, for He hears, and Spirit with Spirit can meet- Closer is He than breathing, and nearer than hands and feet. God is law, say the wise; O soul, and let us rejoice, For if He thunder by law the thunder is yet His voice. Law is God, say some; no God at all, says the fool, For all we have power to see is a straight staff bent in a pool; And the ear of man cannot hear, and the eye of man cannot see; But if we could see and hear, this Vision-were it not He?

Omond uses Tennyson’s poem as an example of Triple Time. One can hear it by the predominance of anapests and dactyls, despite the variations and displacements, even despite its iambic beginning.

“The measure is clearly the same,” says Omond, “though the syllables are fewer, and this implies that the periods contain silence as well as sound.”15

This makes sense if we think of meter in terms of music. A song in 4/4 may have four quarter notes per bar, or it may have three quarter notes and a rest. The idea of metrical pause was something that never came up in the poetry classes or workshops I took in college, most likely because it complicated the sense of what a foot was supposed to be. But this is only a problem if we think a line is identical with its syllables, which it’s not. It isn’t how good poets write, anyway. Consider Shakespeare’s line

Stay, the king has thrown his warder down! (Richard II, I.iii)

Here we have five stresses but only nine syllables. In one sense the line can be said to be shortened and irregular, but in another sense its measure is still equal to the measure of all the other lines, because it has a metrical pause after “Stay.” The same thing happens in Marlowe’s line

What is beauty, saith my sufferings then? (Tamburlaine, Part I, V.ii)

The time measure can be equal across lines even when syllabic variation is present. Omond gives as an example of this Robert Browning’s “Cavalier Song.”

Kentish Sir Byng stood for his King,

Bidding the crop-headed Parliament swing.Here an obvious and necessary suspension of sound after the “Byng” in the first line seems in the second line exactly filled up by the word “headed.” Omit this word, and the two lines are of practically identical structure:

Kentish Sir Byng … stood for his King,

Bidding the crop- … Parliament swing.16

To write good verse, in other words, is not to have a mathematician’s hand for counting syllables, but a musician’s ear for time. It is to hear the time proceeding underneath the syllables, and play with these elements in relation to each other.

A bar of 4/4 may have four quarter notes, or it might have two half notes, or eight eighths. The notes might fall on the beat or they might be syncopated and fall between the beats. The notes may be played fuller or weaker. Such is the case of two lines of Milton, which are set in the same iambic meter yet produce two very different sounds.

Rocks, caves, lakes, fens, bogs, dens, and shades of death. (P.L., II. 631)

And I shall shortly be with them that rest. (Samson Agonistes, 598)

The first line is ‘fuller’ and entirely occupies the time space relative to the second line. How else can the two be reckoned to be in the same meter unless we understand that meter is not the syllables themselves, but the time they occupy?

The measure, then, may be occupied by syllables or metrical pause. Words, too, may have more or less weight (what we think of as quantity), so that a phrase like “more room” may be equal in time with the phrase “in the room.” More words of lesser weight might ‘crowd’ a period, so that a line is ‘extrasyllabic’ yet still keeps its time. It’s possible, for example, to have Double Time with periods of more than two syllables. Omond gives as an example of this a line from Swinburne’s play, Marino Faliero, written in iambic pentameter.

Thou art older and colder of spirit and blood than I.

The line contains fourteen syllables, yet the play being set to heroic verse, it’s easy to hear how such a line could still be read in Double Time. The meter tells us how the words should be compressed and read. Swinburne’s poetry is characteristic of this technique of filling a meter to the brim with extra syllables.

Allured of heavier suns in mightier skies;

Thine ears knew all the wandering watery sighs

(“Ave Atque Vale”)

With sense more keen and spirit of sight more true

The domes, the towers, the mountains and the shore

(“A Sequence of Sonnets on the Death of Robert Browning”)

Prolegomena to Any Future Meter

By thinking of meter in terms of time, we broaden our understanding of metrical effect by considering the interplay of time, accent, and quantity. One of the ways in which a poem is successful in its given meter, according to Omond, is if its variation brings into relief, rather than obscuring, our perception of underlying uniformity.

When syllabic variety overpowers temporal recurrence a line ceases to be metrical. But, short of this, any sort of irregularity—whether in the bulk of syllables, or their stress-value, the rate of their succession, their partial or even complete suppression—seems capable of being so handled as to gratify our ears.17

This seems to me a good way of evaluating verse according to its meter. And it’s a great aid to writing poetry, too, to consider the time a poem is set to and how one might play with the elements of prosody in relation to that time.

The other day I was working on a poem for my series on Rome. It was a dramatic monologue in blank verse, and I came up with the lines

My lot is here in Corinth now, among

the red rock and limestone cliffs of the sea.

It worked fine, but then I took out the “now,” and found that I liked it much better.

My lot is here in Corinth, among

the red rock and limestone cliffs of the sea.

Something about the change in the regularity of the meter at that moment gave the right character and color to the line. In the context of the poem the speaker pauses after the name “Corinth” because it’s the name of the city where they live now, but not the city they want to be living in. The pause after “Corinth” indicates something about the hesitation the speaker feels when they admit they’re no longer living in their homeland. It’s a small change, but I find it effective. It breaks the rhythm in a motivated way. If I were still in college, and still a young poet, I would think I had to have the syllable in there to satisfy the meter. But since reading Omond’s work, I have a better sense of time. I can remember to consider the true function of meter, and write with the ear and not always with the rule.

We Live in Time. (2024). Starring Andrew Garfield and Florence Pugh. A solid 6/10. Very mid.

Ricoeur, Paul. The Rule of Metaphor. Routledge Classics, 2003.

Although they’re no less appreciated. Certainly musical instruments have traditionally accompanied verse.

I once got the lead in our high school play, my first and only outing as a theater kid. I was supposed to have some brief singing parts, as the play was a comedy based on a tenor, but after my teacher took me to a couple of practice sessions with her music instructor friend at the university, she decided to cut out the singing parts altogether. I was told to mime the lines, and she would fade to black.

I got more acquainted with music, as it happens, by learning how to dance.

No judgement against any of them. In fact it was my sophomore teacher who first got me interested in poetry. And now, ironically, I teach sophomores myself. How strange is life.

This happened in a class I took on Milton in grad school. We couldn’t seem to say much more than, “It’s written in blank verse, but not always.”

A Study of Metre. T.S. Omond. Lemma. 1903. p 4.

ibid. Introduction. xi.

ibid. p 20.

Although they are not identical. Omond makes clear several times that music is not identical to verse, and that we should not try to find a one-to-one correlation between musical notation and verse. While music employs pure symbols, verse is based on speech. But they are closely related, and we can use one to get a sense for the other.

A Study of Metre. T.S. Omond. Lemma. 1903. p 53.

He does discuss the possibility of other times, like Quadruple Time, but I’ll be focusing on Double and Triple Time for now.

In his book Milton’s Prosody, Robert Bridges is almost forced to admit, while discussing the variation in Milton’s lines, that “Perhaps this condition of things is expressed by saying that the rhythm overrides the prosody that creates it. The prosody is only the means for the great rhythmical effects, and is not exposed but rather disguised in the reading.” That Bridges believes the rhythm “overrides the prosody that creates it” seems to me an example of trying to the fit the poem to the rule, and not the rule to the poem.

A Study of Metre. T.S. Omond. Lemma. 1903. p 54.

ibid p 12.

ibid p 57.

Hi Robert, nice to meet you! I happen to know a lot about poetic meter: in bouts of ADHD hyperfocus I studied it obsessively (I even know a little about its historical development), and I have a very practised, attenuated ear. I've also written many posts on meter (first on Wordpress, then Quora, and I've contributed to many discussions on particular poems here on Substack).

I have...a *lot* to say in response to your post! Hard to know where to start!

One thing I'd like to clarify, so I can tell to what extent we're on the same page: being as specific as possible, how would you define the difference between an accentual meter and an accentual-syllabic meter?

I'll share a few of my old posts that are directly relevant to some of your comments, and some of the passages you've shared.

The lines you quote from Richard ii and Tamburlaine are headless: they omit the opening offbeat. Elizabethan/Jacobean dramatists employed the occasional headless line for expressive effect. I took a deep dive into exploring headless lines & meters in this post - in which I *also* discuss the absolutely pervasive assumption that metrical templates rise or fall (they do not! It is only at the very beginning and end of a line that a metrical template has a bearing on rising or falling patterns): https://qr.ae/pGeXBo

Speaking of Tudor dramatic verse in regards to your line, "My lot is here in Corinth, among", where you omitted the word "now", creating a natural pause after "Corinth" - yep, Shakespeare would have recognised this metrical technique too! You omitted a beat (in this instance, the 4th beat in a pentameter line). This is a technique he employed *very* sparsely, but to great effect: I provided examples in this post (in the section on "Missing Syllables". By the by, I have since abandoned the Greek terminology I used for many of the variations I describe in this blog, in favour of descriptive English terms, e.g. I now call a "choriamb" a "swing"): https://wp.me/p6PiU4-T

Here's a wonderful example of a phantom beat from the pen of Sylvia Plath: https://qr.ae/pAYyrV

Milton became just a little more experimental with his meter in the second half of Paradise Lost, but the main reason modern readers can find his lines hard to scan is because he was so bold with his contractions. The same is true of late Shakespeare, and I explored the contemporary principles of expansion and contraction in this post: https://wp.me/p6PiU4-pR

As it happens, I once provided a scansion of the opening sentence of Paradise Lost in response to a Quora question (note that I only marked beat placements; for simplicity, I ignored heavy offbeats and light beats, even though such variation plays a huge role in expressive effect): https://qr.ae/pAYygC

Within that scansion I *italicised* beat displacements, and the technical principles of beat displacement within iambic meter are incredibly important to understand when discussing or analysing meter. I cover those principles here (I think of this as my bread and butter post when it comes to communicating the technical principles of iambic meter): https://qr.ae/pGeXLZ

It's also important to distinguish between tight traditional metrical variation (which I covered in the above post), less orthodox variation (such as omitting syllables, which I covered in the first Wordpress post I linked), and loose variation. I compared two Robert Frost sonnets at the end of this post, both of which employ anapests - one very sparingly, the other liberally: https://qr.ae/pY0nT0

I briefly discuss the rhythmic properties of the 5-beat pentameter at the end of this post (as well as some other useful tips & links for beginners): https://qr.ae/pvC4Jn

And, finally, here I provide a photographic example of my own approach to scansion: an approach I find nuanced, tight, logical and consistent, and far more intuitive than simply chopping up the line into individual "feet": https://substack.com/profile/16615725-keir/note/c-101889426?utm_source=notes-share-action&r=9w4rx

Oh, gosh, that's a lot! I hope this hasn't been presumptuous of me, and that at least some of what I've shared is of interest to you! It's a fun topic, and I enjoy discussing it!

"I admit I was once confused by the way that rhythm in a poem could continue even when the feet that made it up were replaced. I lay the blame partly on my tone deaf childhood. I was terrible at music. I couldn’t keep a beat to save my life, and I still have trouble distinguishing notes. I have whatever the opposite of perfect pitch is.4 So, when I was in high school, I could hear the lexical stress in words, but not always the rhythm of the lines my teachers would read aloud, unless they exaggerated the accent. “the WOODS are LOVEly DARK and DEEP / but I have MILES to GO beFORE i SLEEP.” But when their voices fell back into something like the normal cadence of speech, the sense of the rhythm would fade."

This is me. I also struggle with scanning poetry. When I took poetry classes in college I had my best friend scan my poems for me when we needed to do that for homework. I can talk about the effect of different scansion techniques once the line is scanned, but I still struggle to do the scanning unless the line is very regular iambic pentameter.

This is probably not unrelated to my gravitating towards writing free-verse. This and my early and passionate love for T.S. Eliot.

I do like and appreciate formal, metrical verse. I just don't necessarily think that way when I write. Though I do have a sense of the sound and rhythm of the lines I write. I'm just never sure whether they sound the same way to the reader that they do to me. I've always found the whole thing a bit mystifying.

That said while I find the *idea* of Ormond's approach as you describe it freeing, I'm not quite sure I can really get the idea of syllables filling up time either. That doesn't seem much less mystifying. Maybe because I still find musical time mystifying.

Mostly I stick to loose syllabics. Sometimes lines want to be 9 or 11 instead of 10 and I let them. But I'd be hard pressed to justify why. And maybe I only think it works while people who have a better sense of rhythm are left scratching their heads and wondering what's wrong with me.