Not with a bang

A conformal picture of poetry

I

For Roger Penrose, the universe’s beginning is its end.

The Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist’s model of the universe, called Conformal Cyclic Cosmology, proposes a universe that is iterative, perhaps infinitely so. In this model, our universe is merely one in a succession of universes Penrose calls aeons. And the end of one aeon is the beginning of another.

Penrose outlines his theory in Cycles of Time (2010), and though I’ve only ever managed to make it through half the book before the math defeats me, the prose itself is highly readable for a layperson.1 One can anyway find him summarizing his theory on plenty of YouTube videos and podcasts.2

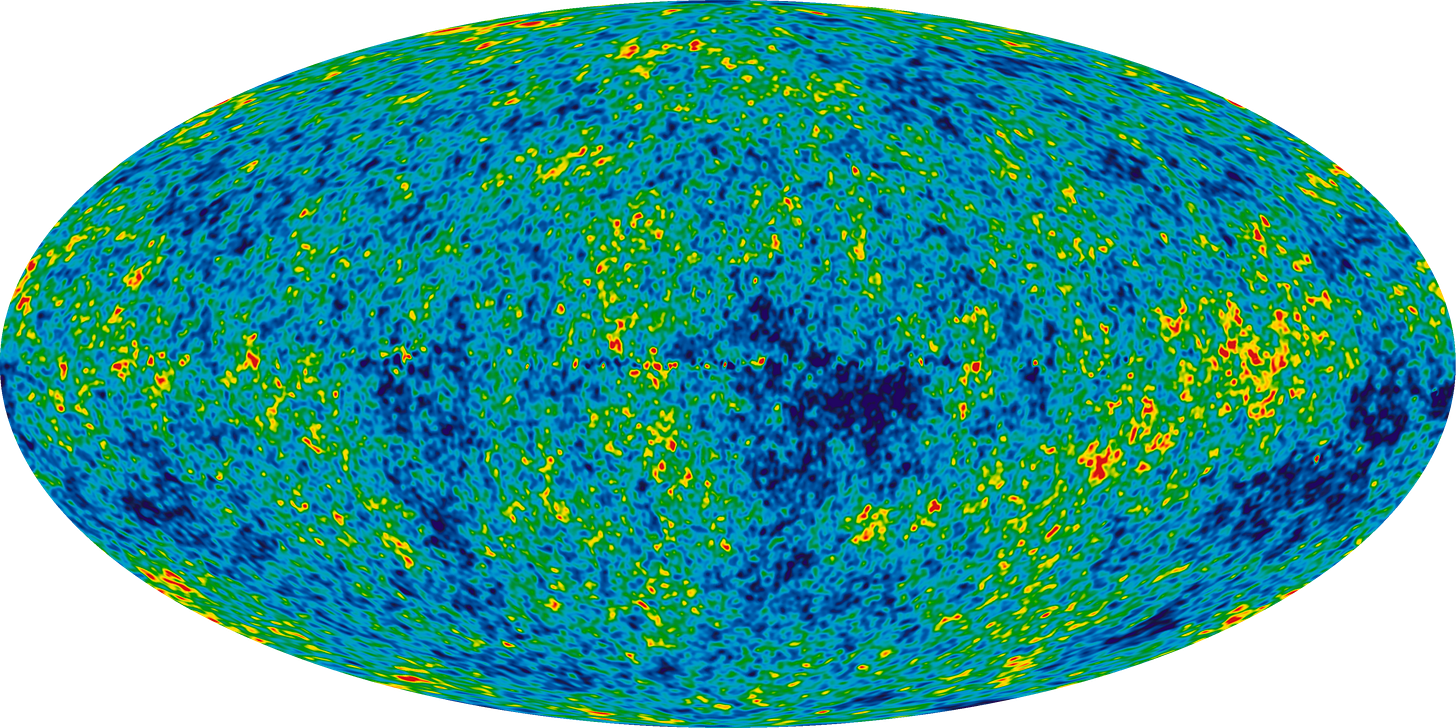

Penrose’s model differs from the more conventional view in astrophysics that places the beginning of everything at the Big Bang, the singularity out of which all matter and time was born. Scientists infer from the expansion they currently observe that everything must’ve once been contracted into an infinitely dense and hot point. Part of their reason for thinking this, in addition to Einstein’s theory of General Relativity and Hubble’s observations, is the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), the faint radiation that fills our observable universe. This radiation is a relic left over from the early expansion of the universe.

What’s interesting about the CMB is that the radiation is remarkably uniform. The early universe was in a state of thermal equilibrium, which is the same thing as saying that it was high in entropy and maximally random. Interestingly enough, this is one of the possible ends hypothesized for the universe, and part of the reason for Penrose’s argument for cyclical cosmology.

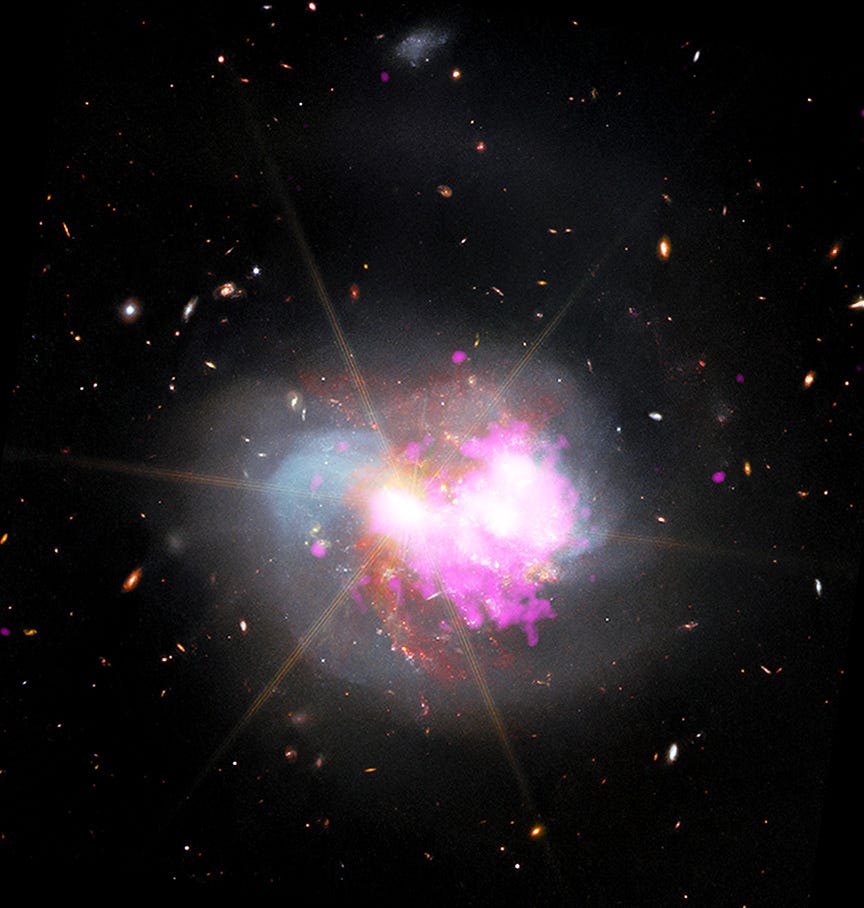

The second law of thermodynamics states that entropy always increases. Think of a fireplace in a room, how the heat disperses, moving into areas of cold until the temperature of the room reaches an equilibrium and the wood is consumed. Now think of the entire universe. In the remote future, all the stars will have exhausted their energy and gone out, all life will have ended, all matter will have been swallowed up by black holes. The black holes themselves will have exhausted their energy, too, through Hawking radiation, and disappear “with a pop,” as Penrose says. The accelerated expansion of the universe will have dispersed what little energy remains, until it reaches the same state of thermal equilibrium in which it began. This hypothesized end of everything is called Heat Death, a time when no energy exists anywhere to do anything meaningful. Maximum entropy. Maximum dissipation and disorder.

But what appears to be the end of the cosmos will actually look like a beginning, according to Penrose. Without mass, without energy, there will be nothing to measure time by, and no sense of space.3 In such a state the universe will “forget how big it is,” and infinity, for a photon, will seem instantaneous. There will be no difference between expansion and compression, and in this way a universe expanded into oblivion will seem no different than one infinitely compressed.

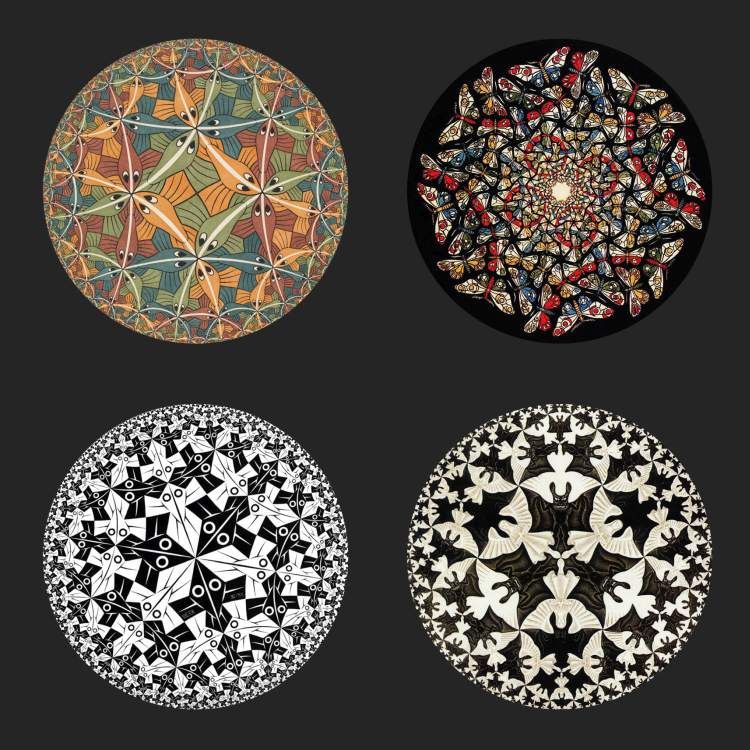

The analogy Penrose frequently uses to illustrate this is Escher’s Circle Limit series.

Escher’s images are conformal maps of hyperbolic geometry. They are analogous to a universe with negative curvature (a 'saddle-shaped' universe, which ours might be) with the edges of the circle representing an infinite horizon. Yet the figures inside the images don’t experience themselves as being bigger or smaller than each other, for although their sizes change, their angles are preserved. In such a space one would not notice a change moving from the edge of the circle to its center. We could in theory 'expand' the figures on the edges to see them better, and the figures in the middle would 'contract.' The sizes would change while the angles would stay the same.

We could also imagine going around to the 'other side' of the circle. Penrose says this would be analogous to seeing the previous aeon of a preceding universe. We would be peering behind infinity to find the universe’s beginning in its end.

II

The history of English poetry, like that of the universe, proceeds from order to disorder. Its poetic material and energies, like all matter, obey the second law, and are always increasing in entropy.

Eliot called this the “dissociation of sensibility” in his essay on the Metaphysical poets. Remarking on the difference between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, he describes the poets of the former as having “a mechanism of sensibility which could devour any kind of experience.”

[I]t is the difference between the intellectual poet and the reflective poet. Tennyson and Browning are poets, and they think; but they do not feel their thoughts as immediately as the odour of a rose. A thought to Donne was an experience; it modified his sensibility. When a poet’s mind is perfectly equipped for its work, it is constantly amalgamating disparate experience; the ordinary man’s experience is chaotic, irregular, fragmentary. The latter falls in love, or reads Spinoza, and these experiences have nothing to do with each other; […] in the mind of the poet these experiences are always forming new wholes.4

In Donne and Chapman and Henry King there is, for Eliot, “a direct sensuous apprehension of thought” and a unity of thought and feeling which made possible the widest variety of experience in verse. A richness of associations and conceits, simplicity and elegance of language, and complexity of structure, were all signs of a high fidelity to thought and feeling. But by the seventeenth century that mechanism was fragmenting, such that “while the language became more refined, the feeling became more crude.”

The sentimental age began early in the eighteenth century, and continued. The poets revolted against the ratiocinative, the descriptive; they thought and felt by fits, unbalanced; they reflected.

This process would continue into the nineteenth and twentieth century. Eliot, ironically, would become responsible for a further dissociation. The modernist manner, with its fragmentary style, its obscurantism, its allusiveness and difficulty, would further detach feeling from thinking. Yvor Winters once remarked how strange it was how Eliot had been so right in his diagnosis and yet had come to the exact wrong conclusions about the way forward, advocating in the same essay that poets in the twentieth century should become “more allusive, more indirect, in order to force, to dislocate if necessary, language into his meaning.” What happened was not a dislocation of language into meaning, but from it. Postmodernism, with its various projects of decentering and deconstructing, with its emphasis on the spontaneous and the irrational, would increase the entropy of the poetic system at an accelerated rate, from Creeley’s “Meaning is not importantly referential” to the indeterminacy of Ashbery, from the amateurism of the Beats to the impenetrability of the language poets—the major movements of the second half of the twentieth century were like that dark, repulsive energy rapidly expanding the universe and repelling galaxies away from each other.

III

It’s interesting that Eliot calls Tennyson a poet of reflection, a poet who writes removed from his feelings. Tennyson’s friend Arthur Henry Hallam was of the opposite opinion. Writing a review of Tennyson’s first major collection for the Englishman in 1831, he calls Tennyson a “Poet of Sensation,” and classes him among Keats and Shelley.

They [Keats and Shelley] are both poets of sensation rather than reflection. Susceptible of the slightest impulse from external nature, their fine organs trembled into emotion at colours, and sounds, and movements, unperceived or unregarded by duller temperaments. […] Other poets seek for images to illustrate their conceptions; these men had no need to seek; they lived in a world of images; for the most important and extensive portion of their life consisted in those emotions, which are immediately conversant with sensation.

For Hallam, the Poets of Reflection were Wordsworth and Coleridge, which might seem odd to us today, if we recall Wordsworth’s famous dictum that all good poetry is “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.” But we often forget the second part. “For all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings; but though this be true, Poems to which any value can be attached, were never produced on any variety of subjects but by a man who being possessed of more than usual organic sensibility had also thought long and deeply.”

Tennyson, in contrast, was a poet of “impassioned song, more easily felt than described, and not to be escaped by those who have once felt it.” Of course Hallam is speaking of the younger Tennyson, the Tennyson of the “The Kraken” and “The Lotos-Eaters,” while Eliot presumably had in mind the Tennyson of The Idylls and “Ulysses.”

But Hallam, like Eliot, also remarks on a “dissociation” in the poetic tradition, what he calls a “diffusion” of the powers of poetic disposition.

It would be tedious to repeat the tale, so often related, of French contagion, and the heresies of the Popian school. With the close of the last century came an era of reaction, an era of painful struggle, to bring our overcivilized condition of thought into union with the fresh productive spirit that brightened the morning of our literature. […] Those different powers of poetic disposition, the energies of Sensitive, of Reflective, of Passionate Emotion, which in former times were intermingled, and derived from mutual support an extensive empire over the feelings of men, were now restrained within separate spheres of agency. The whole system no longer worked harmoniously, and by intrinsic harmony acquired external freedom; but there arose a violent and unusual action in the several component functions, each for itself, all striving to reproduce the regular power which the whole had once enjoyed. Hence the melancholy, which so evidently characterizes the spirit of modern poetry; hence that return of the mind upon itself, and the habit of seeking relief in idiosyncrasies rather than community of interest.5

These poetic energies, the sensitive, the reflective, the passionate, isolated themselves into separate spheres of agency. Where once a poet might be said to possess a variety of poetic powers, and exercise them according to the demands of the subject, now their range of abilities is narrower, their poetic disposition merely a matter of temperament or subjectivity or identity. What we end up with, as Eliot remarked elsewhere, is “only a successive alternation of personality.”6 The single thread of tradition, having frayed and split into various strands, different movements, schools of thought, approaches, attitudes, disciplines, lenses, divides and subdivides, growing ever finer and more diffuse. Entropy increases, and disorder grows.

IV

Whether or not one agrees with Eliot or Hallam’s view of things, it’s readily accepted that we live in a period of cultural stagnation, the understanding of which is one of the few things we share collectively as a culture. In art there’s the sense that no change is possible, no great movement is capable of taking hold, given the ever narrowing social and material horizons, and the deterioration and fragmentation of new technologies that art is continually subjected to. Poetry is destined to be scattered among its ever shrinking genres, its niches more and more isolated, the space between making communication impossible. And the end is a slow diffusion of what little energy remains to be exhausted. We have reached a state, it seems, of highest entropy, the Logos that animates language and imbues it with sense having become maximally disordered, both intentionally and unintentionally.

Yet it is possible to imagine such a state as the precondition for the emergence of something new and remarkable. As Penrose envisions the end of the universe as the beginning of another, so we can envision the inevitability of great poetic production out of an otherwise sterile environment.

Surely the great poet is, among other things, one who not merely restores a tradition which has been in abeyance, but one who in his poetry re-twines as many straying strands of tradition as possible.7

Tradition, though it obeys the laws of thermodynamics, is not bound by the same massive timescale as the universe. It may be reborn in no short time, and may even be found to have begun already. In Penrose’s model, a universe expanded into oblivion looks no different than one infinitely compressed to a single point. The difference between the end of one aeon and the beginning of another is merely the invocation that there be light.

His 2004 The Road to Reality is also very readable, if one skips over the difficult parts. There he gives a comprehensive overview of everything we know in physics so far.

On Closer to the Truth, or the Joe Rogan Podcast, for example.

As I understand it, it’s not that the universe would be massless, but that whatever mass did exist would be negligible, so inconsequential and isolated that it could not meaningfully affect anything. Photons, massless themselves, would move through such infinite and empty space instantly, such that an eternity would pass until the mass they did come upon would usher in the dawn of the next aeon. Or something like that.

“Selected Essay: The Metaphysical Poets” from The Collected Prose Vol 2 (Faber).

“On Some of the Characteristics of Modern Poetry, and on the Lyrical Poems of Alfred Tennyson” from the Norton Critical Edition of Tennyson’s Poetry

The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism

ibid.

Brilliant work, thank you for sharing.

You may enjoy the writing of Alan Lightman, who is both a physicist and great writer. Particularly the short books Einstein's Dreams and Mr G. Very similar themes explored, visually and characteristically.

Nice analogy, and if I got your conclusion right (there may (?) be a move from an indivdual-based poetry based on a personal voice to a more universal poetry using a variety of voices and traditional forms based on the subject) a very hopeful one. Especially for doggerel writers like me who bounce about using whatever form (or lack thereof) seems to suit me in the moment.