This is a sister poem to an earlier piece, “Vixerunt.” Both poems deal with the political battle between Cato and Caesar, as well as the larger conflict between the optimates and the populares that played a key role in the downfall of the Republic.

The previous poem narrated the fallout of the Catiline conspiracy, when several of its members were put to death, at the urging of Cato, and despite the opposition of Caesar.

Four years pass, and Caesar has returned from Spain with newfound political strength. He has won the consulship, and has, in secret, formed an alliance with two other powerful citizens, the wealthy Crassus and the military hero Pompey. His patience with the bureaucracy and subversions of the Senate at an end, Caesar, instead of fighting Cato directly, takes his complaint to the people, and emerges victorious.

The two episodes are mirror images that serve as the fulcrum to Caesar’s rise to power. His political ambitions fulfilled by the end of 59 BC, including a number of reforms that win him the favor of the plebeians and the equites, Caesar will leave for Gaul for eight years and return to Rome a legend and a harbinger, igniting a civil war that will leave him the sole conqueror of the world.

Populus

When Cato said they ought not pass the bill

that Caesar brought, as consul, to the Senate,

the conscript fathers could not match his will,

for all but he seemed willing to commit.

So obviated was dissent with skill

that any opposition, they thought, seemed

unreasonable. Everyone had had their say.

The lands distributed among the commons

they deemed fair. And much of it going

to those well-deserved veterans of Pompey.

But Cato demurred, palavered, and when

removed by force, the sensible protested.

It isn’t done, they scoffed and disapproved.

A man like Cato cannot be arrested!

So Caesar relented, yet was not moved,

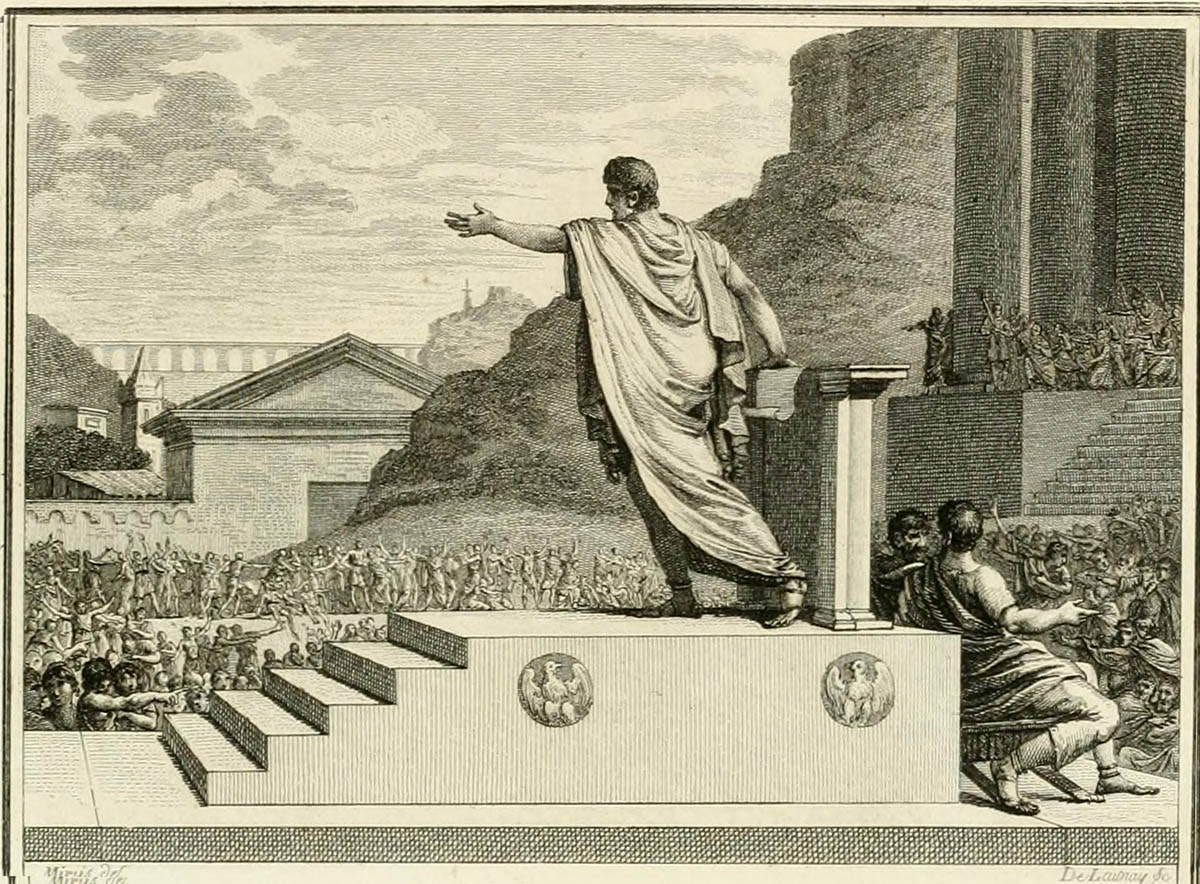

and went instead to win the favor of the plebs.

How right you were in your suspicions, he said.

The best look down upon you with contempt.

They would deny what was in both your interests,

forgoing that to which they gave consent,

for no other reason than because it was

to your advantage—because they hate you.

So abandoned are they to their vices

they would obstruct what obligation

to office and State demands they do.

Oh, there was a time when the best ruled.

The wisest, strongest, most obdurate in virtue.

And to oppose them was to seem the fool.

Our fathers, and theirs, but not us, knew.

We are slaves to the wicked and the cruel.

It were a worse shame to suffer tyranny

at the hands of craven, useless elites,

than to live by the strong despot’s mercy.

The latter do violence with bared teeth,

the former with a feigned superiority.

With lavish banquets and private ponds

they nurse their bruised inferiority,

and hang from courtyards unearned fronds

to hide disgrace and dereliction of duty.

Yet they withhold from you their bonds?

The City prospers from its work abroad,

its people stand to profit from the spoils,

yet they would circumvent the rule of law

to keep for themselves what, by your toils,

you rightfully earned? Oh envy is fraud!

A wasting leech! An abattoir that sells

the lean cuts of its undigested spleen

and feeds itself on the best to bursting.

Your rights to them are but another meal

prepared, on technicalities, to steal.

But here is Crassus, and here great Pompey,

back from his war that’s made us all rich.

If it’s a fight they want, says Crassus first,

we shall have the final word. And Pompey,

If they draw theirs, I, too, draw my sword.

From the porchsteps of the Dioscuri

he raises it up, and the face of the blade

catches the sun, flashing for all to see.

Now Cato and his supporters come,

pushing through crowds to the podium.

Enough, enough! Bibulus tries to say.

The skies are being watched for omens.

It is against the law to assemble today.

They hiss and sneer. Some words are said,

and a pail of dung is dumped on his head.

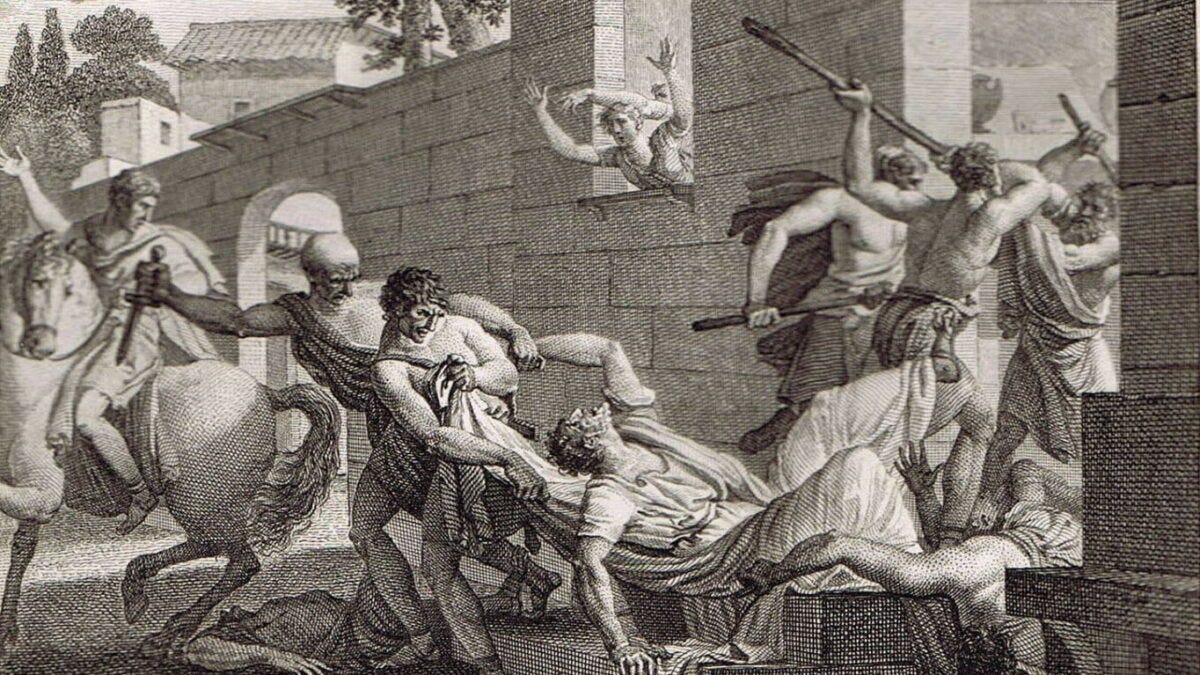

The tribunes who came with Cato are shoved,

their fasces ripped from them, and snapped.

They fight, then flee, as stones are hurled at

their backs. Cato is chased but left unharmed

by what remains of their propriety.

In time the bloodshed spills into the streets.

His house sacked, Cicero, at night, flees.

The factions formed, the dissolute Clodius

on one side, on the other, the gangster Milo.

To Cyprus they dispatch the noisome Cato.

The Lares hide their faces at the crossroads

as brawls break out at every college tavern.

Women do not walk the alleys alone.

The men, incensed to violence, are too eager.

That year was the year of Julius and Caesar.

Here you are doing what you do best: Taking the historical record, digesting, interpreting, clarifying, hammering into measured, dignified verse. You delight and edify.