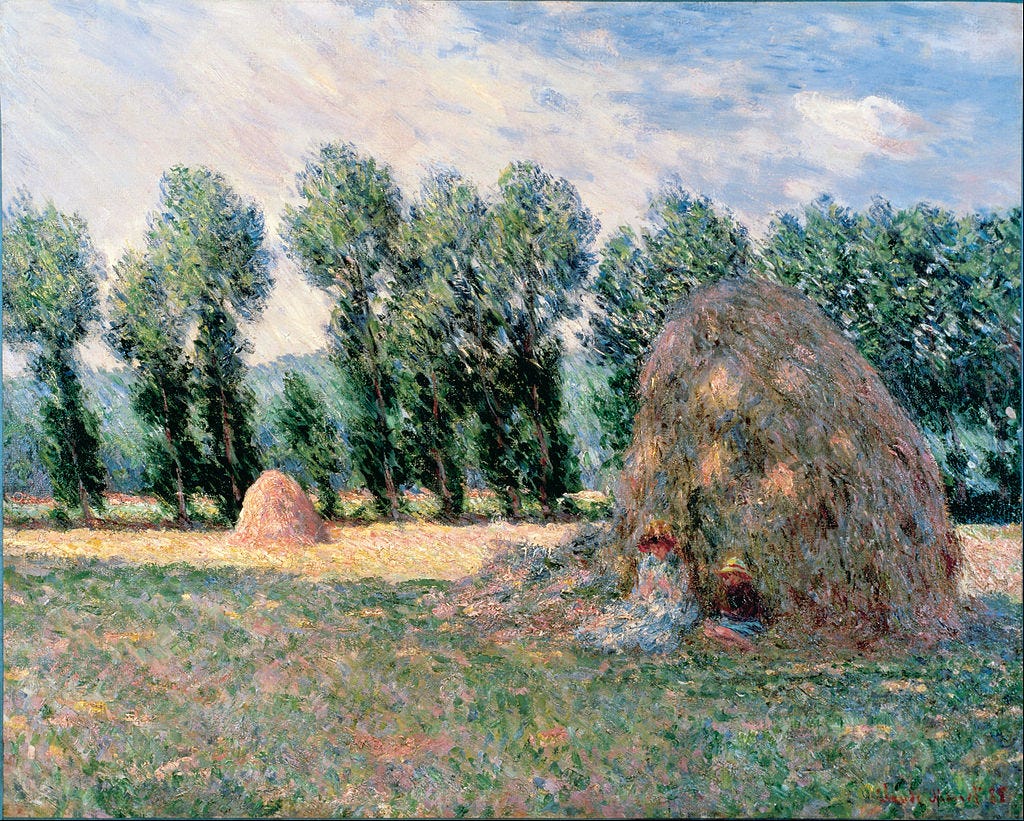

“To contemplate comes from “templum, temple, a space for observation, marked out by the augur.” It means, not simply to observe, to regard, but to do these things in the presence of a god. And to meditate is “to keep the mind in a state of contemplation”; its synonym is “to muse,” and to muse comes from a word meaning “to stand with open mouth”—not so comical if we think of “inspiration”—to breathe in. So—as the poet stands openmouthed in the temple of life, contemplating his experience, there come to him the first words of the poem.”

—Denise Levertov

I find etymology very compelling.

Whether in dialogue or argumentation, or in Levertov’s case, explication, our intentions to communicate anything come down to the meaning invested in the words we use.

What a word means is partly a matter of its use, each speech-act placing it in a new context and so slightly reconfiguring its contours—and partly a matter of what sense it has already invested within it.

Each word is an artifact, an ancient pottery stumbled upon and then made use of.

As if finding some Pre-Roman pottery

while hiking the Apennines of Tuscany

you brought it home and simply

added it to the dirty pile in the sink

to be washed and used as with everything.

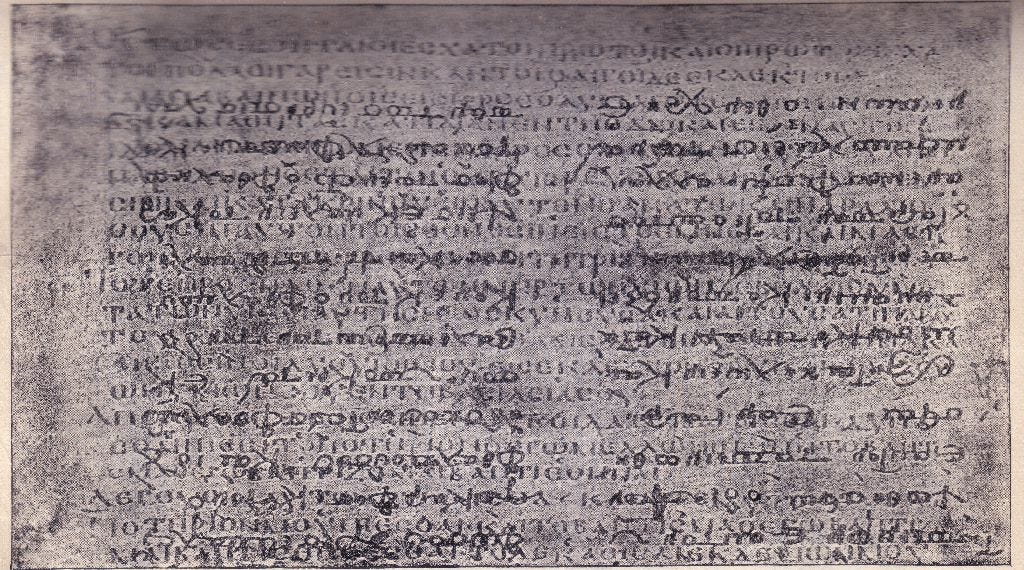

To use a more popular metaphor, each word is a palimpsest, a scroll or fragment of a scroll written on and written over countless times. The word itself appears in bold, scrawled repetitively into the scroll to stand out against everything else. Underneath it, all the individual instances of its usage, traceable if sometimes barely legible, that form a valence of denotation and connotation.

What recourse to etymology gives one is what Charles Bennett called Logical Depth. I wrote about Logical Depth in a previous post.

Logical Depth measures the process that leads to information. It’s a measure of what it took to generate a message, the time and effort of calculation. The more work that goes into producing a message, the more depth there’s said to be.

Bennett was responding to the work of Claude Shannon, the father of Information Theory. Shannon’s theory, interested only in the transmission of a message, was unconcerned with its semantic content. Bennett wanted to develop the idea of meaning within the field as a way of understanding what, if anything, makes information meaningful.

For Bennet, what makes information meaningful is all the work that went into producing it. Logical Depth measures that discarded information that’s still readable in a message.

That work, all that information that went into producing the message gets discarded, although it’s still there, as context. It’s still in the message (assuming there is logic to the way the message was made) and can be called upon, summoned again, presumably, to further compile and refine the message into a still clearer one. To talk about Logical Depth is to talk about that process of refinement.1

This recalls the image of the word as a palimpsest, for the depth contained within a word is the record of its use, its being used and reused. To draw upon it, then, to call up such history as Levertov does imagining the poetic process, is to draw out that depth of meaning inherent in the words themselves. The sense is deeply satisfying. Satisfying because clarifying and edifying. Our sense of words is renewed by the rediscovery of their primitive use, and sense itself is reawakened, reestablished, restored.2

’s recent post Could Beowulf See Blue? which looks at the history of the word blue in the English language, is another good example of using etymology to great effect. By drawing on it, tracing the uses of various color words, Gorrie is able to convincingly reconstruct the cultural and psychological conditions of the people who first used them. He rediscovers the original sense of the words, traceable in the history of their use, and reimagines for us the perceptions of the people who used them.The exercise is so pleasing to the imagination, too, because the inspiration it engenders, by virtue of understanding what a word once meant, is the same creative impulse that first produced it. We feel something very akin to what the poets felt when we learn the etymology of a word.

Consider the word window. A rather utilitarian word. Functional, devoid of color and connotation. Yet when we consider the roots of it, from the old Teutonic vindauga, a kenning of vindr "wind" and auga "eye", does it not suddenly seem new again? To know it once meant something like “the wind’s eye”, are we not inspired to imagine the mind of the person, and the people, who must’ve first experienced the hole in their house as an eye of wind?

The poets were the creators of such words, and we the inheritors. Owen Barfield, the philosopher and fellow Inkling, reminds us that, having inherited words, whenever we use them, we are participating in that word’s history, its story. Even those words we use which seem to us so literal, so devoid of metaphorical suggestion and historical contingency that they must mean only what we intend them to mean.

Much fun has been made of medieval philosophy for discussing such matters as how many angels can stand on the point of a needle, and whether Christ could have performed His cosmic mission equally well if He had been incarnated as a pea instead of as a man. The growth of a rudimentary historical sense has, it is true, made it fashionable lately to take these ancient thinkers rather more seriously, but it is still rare to find a philosopher or a psychologist who fully comprehends that he is consuming the fruits of this long, agonizing struggle to state the exact relation between spirit and matter, every time he uses such key-words of thought as absolute, actual, attribute, cause, concept, deduction, essence, existence, intellect, intelligence, intention, intuition, motive, potential, predicate, substance, tendency, transcend; abstract and concrete, entity and identity, matter and form, quality and quantity, objective and subjective, real and ideal, general, special and species, particular, individual, and universal. ‘Free will’ is the translation of a Latin phrase first used by a Church Father, and ‘argumentum ad hominem’ is an example of a scholastic idiom which has remained untranslated. Many of these words, it is true, are in the first instance Latin translations of Greek terms introduced by pagan writers before the days of the Schoolmen; some, like quality and species, by Cicero himself, and others, like accident, actual, and essence, by later Latin writers such as Quintilian or Macrobius. But it must be remembered that, even in these cases, the words, as we use them today, are not mere translations. By their earnest and lengthy discussions the Schoolmen were all the time defining more strictly the meanings of these and of many other words already in use, and so adapting them to the European brain that in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries it was an easy matter for the lawyers and for the popular writers like Chaucer and Wyclif to stamp them with the authentic genius of the English language and turn them into current coin. Nobody who understands the amount of pain and energy which go to the creation of new instruments of thought can feel anything but respect for the philosophy of the Middle Ages.3

As I’ve been writing about words, I’ve had in mind the sense which Barfield has of them, as instruments of thought. The poet is that artist who fashions these instruments and figures their use. Not only words, but other instruments of thought such as grammar gives us. A poet may fashion a single trope or a whole style, a way, of speaking. Eliot once said about Donne that he invented an idiom, “a language which less original men could learn to talk, and which they went on talking until they had talked it out.”4

This “talking out” is what necessitates the need for renewal. Language, always in the process of calcifying from its literalness, must perennially shed itself and be refreshed. Its newness is renewal. And etymology renews language by recovering something true about words: how they were once used, and how they might be used again. It is a knowledge that is true by virtue of its depth, and in that way it seems compelling.

In his book The User Illusion, Tor Nørretranders, summarizing Bennett’s ideas, calls all the information that’s been left out of a message exformation. It is the exformation that constitutes a message’s Logical Depth.

There’s something religious about the act of recovering the original meaning of words, the word religion itself coming from the Latin religio, to "relink".

History in English Words. Lindisfarne Books. pgs 139-40.

from a talk given April 4th, 1930, titled “The Minor Metaphysicals” in Volume 2 of his Collected Prose (Faber).

Great short piece. This is really cool for etymology nerds too, about how ancient Greeks saw color, and why it was almost certainly not like we see it today.

https://aeon.co/essays/can-we-hope-to-understand-how-the-greeks-saw-their-world

My children all know that etymology online is one of my favorite websites. They all know too that if they ask me to define a word they will also get the etymology thrown at them as well. Hardly a day goes by when I'm not making one or another of them groan as I read etymologies at them. It's so satisfying to dig down at the roots of words.