In a previous post I looked at Robert Frost’s theory of the sound of sense, and asked the question, “Whose voice is your poetry in?”

Frost was interested in meaning at the level of the sentence sound. The voice, the character, of the way a thing is said, such that it tells us, by its sound, something beyond or underneath the words themselves.

Consider the character of the sentence

I don’t know Margo

To the aural imagination it may sound like several things. A response to the question, “Do you know Margo?” Or a response to Margo herself, letting her know that they don’t know. And the way that one lets her know could take on any number of tones. It could be said questioningly, or with some surprise, or chidingly, with impertinence, as in this expertly delivered line from Christmas Vacation (1989)

Of course any interpretation will depend on the context in which the line appears. It will have been shaped by the poet according to the aural scene he has figured in his imagination.

The deployment and accumulation of sound-postures constitutes what we understand as voice, the voice of the character and the voice of the poet (if there is such a distinction in poetry today). Voice is perhaps the quintessential figure of sound. All other figures of sound are to some degree understood through it. The extent to which anyone can imagine how something ought to sound depends upon ‘hearing’ the imagined voice that says it. Voice is the medium for sound in language.

The Language of the Birds

Voice is a matter not only of what is said, but how it’s said. While that statement may seem like something of a platitude, it is shallow only to the extent that we do not plumb its depths any further. For the more we consider voice, the more we realize that its effects, partly individual, are yet not entirely of our own making. As I mentioned in the last post, Frost claimed that the music of speech, the sentence sounds, and the sense one has of them, are inherited.

Just so many sentence sounds belong to man as just so many vocal runs belong to one kind of bird. We come into the world with them and create none of them. What we feel as creation is only selection and grouping. We summon them from Heaven knows where under excitement with the audile imagination.1

Coincidentally, in one of Richard Dawkins’ recent lectures for his latest book, he mentions a study done on how American song sparrows learn their songs. Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist, says that sparrows teach themselves when they’re young by “burbling at random, repeating those phrases which match a built-in template of what the song ought to sound like.” In certain types of sparrows, the template is built-in at the level of the genes, so that the sparrow doesn’t even have to have heard another sparrow singing, while in other sparrows it’s acquired culturally, through mimesis.

So, too, do we have our template, and acquire our repertoire of runs, figuring out how something ought to sound, finding an expression adequate for our thought.2 A child grasping at the form of a word with their inarticulate vocals. A student trying to figure out how to say something intelligent, or funny. A writer contemplating the precise way to get down a difficult idea. The sound of the sentence is not only a matter of the words, but how they’re employed. With what tone, what intention, in what order, toward what meaning.

Consider the variations in the following lines, the different sounds they make, the characters of the voices that seem to fit them.

Man is always moving forward

Man has always been moving forward

Man, always moving forward

Man moves forward always

Always forward Man moves

Forward Man, always forward

Moving always forward is Man

Man, he moves forward always

I do a variation of this exercise with my students. I got it from Richard Lanham’s book Style: an Anti-Textbook. Lanham gets it from Erasmus’ De Copia.

What it does is highlight some of the nuances regarding voice. In the example, I’ve tried keeping the lines similar—with my students we’re using synonyms, adding phrases, etc.— But with fewer variations you get a sense of what Frost means when he says that “What we feel as creation is only selection and grouping.” Each version, even with minimal variation, invites a different character to the sound of the sentence. A different character, a different set of circumstances.

The variation, if we hear any at all, is not of our own making. It is in one sense, as we are the ones doing the imagining. But in another sense, what we are imagining is not ours, but belongs to those templates that teach us how a line ought to be said.

The Lexicon of the Birds

Sometimes the idea itself is contained in the sound-posture, and we get at saying it by getting first at the character of the sound. What we’re drawing on then is tradition.

In poetry, as in every art, the tradition we inherit informs our aural imagination. It is that set of templates. The deeper you study the tradition, the more you develop that historical sense which Eliot said was “nearly indispensable to any one who would continue to be a poet beyond his twenty-fifth year.”3 The more one reads, the more one begins to hear poetic predecessors in the lines one reads and writes. And what sounds good, what works, is what has already been taken to be, what has already possessed oneself.

When we’re young we’re mostly possessed, and everything is imitation. Technique, sentiment, sensibility. Most of what we’re doing when we’re young writers boils down to, “How did that person put it?” We are building up our repertoire of vocal runs.

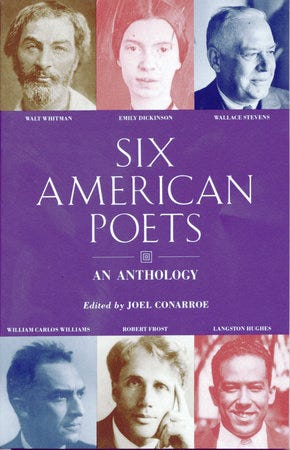

For me it was, at various times, for varying periods of time: Eliot, Frost, Tennyson, Browning, Homer, Shakespeare, Ovid, Baudelaire, Milton, Virgil, cummings, Crane, Goethe, Dante, FitzGerald, Whitman, the Romantics, the Modernists, the Metaphysical Poets, the Augustan Poets, etc.4 Probably the first books that made the greatest impression on me were The Iliad (I still have the Rouse edition I first got in high school) and a Vintage anthology called Six American Poets.

As I continued, the catalogue deepened, the niches grew finer and more varied. The voices clarified as I got better at comparing and distinguishing them. The better ones grew stronger, more distinct. Taste developed. It became easier to select, to weigh, to evaluate.5 We judge by discernment. And when we write we hold up our own voice, if we have one, to those of our influences. Others hold up our voice to their influences, too. In this way one’s poetic voice is never judged entirely on its own merits.

It will be understood in terms of what has come before it. Whether it sounds like something we’ve heard already. Whether it feels too close. Whether it departs in interesting ways from it. Whether it sounds like one’s own.

Therefore what “sounds good” is less subjective than we might suppose, for our judgements are formed by our relationship to those external influences to which everyone is subject: the literary tradition, which is not only cultural but historical, psychological, perhaps even biological. There are things that sound pleasing not because we find them pleasing, but because we cannot help but find them pleasing. And something which we cannot help but find pleasing, which is by definition an essential part of the aesthetic experience, is one’s historical sense in which a work of art is situated. One’s sense for the correctness of an expression, its clarity or obscurity, its grammatical precision or inaccuracy, its just or unjust choice of word, is always partly a matter of tradition. Our aural imagination is inherited, which means that our voice, in so far as we have one, is not ours alone. And whether by nature or nurture, that which we share in common, as society, as civilization, as species, shall be the standards by which we say, “this sounds great, and it is great.”

To cultivate one’s taste according to tradition, then, is a prerequisite, not only of poetic criticism, but of the practice of poetry itself. Put simply, the more deeply you’ve studied the art, the better your appreciation and practice of it becomes.

The Parliament of Fowls

One wouldn’t get such an impression from popular conceptions of poetry today. Many platforms that profess to teach the craft are really concerned with other things. Where relativism prevails, and poetry is synonymous with “self-expression,” all technique becomes mere acts of “self-actualization” and “self-discovery.” Tradition, which is whatever one wants it to be, becomes no more than the most recent and arbitrary reincarnation of oneself.

This isn’t craft but self-help. It’s poetry as therapy, which is fine so far as therapy goes. It’s certainly therapeutic to find an expression adequate to one’s thought. In life, such a thing is invaluable however you acquire it. But whether such approaches to poetry produce anything of any real value, I think the evidence is everywhere to be found on social media.6

The platforms of poets hustling workshops and mentorships aren’t even in the business of teaching students the means to self-expression—if that is indeed the goal—only how to fashion their voices into the personality or style of the moment. And, as Eliot says, if the tradition only consisted in following “the ways of the immediate generation before us in a blind or timid adherence to its successes” it should be “positively discouraged.”

Tradition is a matter of much wider significance. […] [T]he historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence; the historical sense compels a man to write not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with the feeling that the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer and within it the whole of the literature of his own country has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order.7

So we return to the question, “Whose voice is your poetry in?” To even begin to answer this, one first has to read a great deal, until the aural imagination is figured with that repertoire of voices. Then we can hear how our own voice might sound. First imitating, then discriminating, then ordering, until the whole of the tradition speaks to us with clarity. And if we’re lucky, one day, we might speak in our own voice, but it will not have been our own.

Letter to Sidney Cox, Dec 1914.

My instinct is that we do this culturally, through mimesis, but how deep in our cultural history we’ve acquired these sounds seems an open question. Probably their are sedimentary layers, accumulations of meaningful sentences sounds from various epochs in the development of any language.

from “Tradition and the Individual Talent”

I’m speaking strictly of poetic influences, although certainly prose writers can, and do, influence one’s poetry.

It took longer than twenty-five years, but who can keep up with Eliot?

The cult of the noble amateur, to use Rebecca Watts’ phrase, as it turns out, is the cult of the perpetual amateur. None of the young InstaPoets have matured their style. How embarrassing it will seem, then, when a 50yo Rupi Kaur is still writing bad breakup poetry.

from “Tradition and the Individual Talent”

As a retired elementary teacher, all I could think when I read this post title was the change of the phrase with its missing comma. (Illustrated in "Eats Shoots and Leaves" picture book :-). *

"I don't know, Margo."

Thank you for this excellent treatise on reading, reading and reading poetry--and lots of it--whilst we fancy ourselves writers of the same.

(PS tell me about those remarkable vintage bird illustrations!)

*Eats, Shoots & Leaves: Why, Commas Really Do Make a Difference! by Lynne Truss.

As to answer your question for my own concern:

Perhaps you will find this contradictory to your post-perhaps I have also misunderstood my reading but

The only way we might recover from the over-influence of a self- realization culture in writing... Is to recognize that the voice comes from the questions we propose, and unfolds in our ability to articulate them. I do however believe that the craft of discovering this means of expression does come from someplace we might not understand. But only in the way that self expression and self realization is dichotomized with the heart story of our bringing up. In the sense of putting words together everything we know comes to coexist with everything we didn't know we know. I feel this is essential to the passion of craft, not only that but to the passion of honesty, curiosity, exploration and truth as it might broadly embody our insights.

I ones wrote that writing is a way of documenting our world, by creating a miniature depiction of it in all its illusive , and counterly, explicit nature.

My question for you is, Is the journey to a voice meant to build determination to fuel the craft in its entirety, or is it that: As R.M Rilke say's (Summerizing here)... As we seek to look eply into our internal, we will stop asking the external- wether there is value to what we do. Undestanding that we do it for purpose far unfathomable to our craft itself. And what validation (of any sorts) might begin it's potential