I think that his [the poet’s] function is to make his imagination theirs and that he fulfills himself only as he sees his imagination become the light in the minds of others.

—Stevens, “The Noble Rider and the Sound of Words”

The question of the value of poetry today boils down, for me, to a matter of function. Is there something that poetry does that other arts cannot?

That it will survive as a living art and not become a relic of the past depends on its works being (1) useful and (2) exclusive. And while anyone who’s had even a passing knowledge of poetry will be able to grasp its usefulness1, the issue of exclusivity seems a much harder problem. Why should we continue to read and write poetry, especially when much of what’s there, be it the use of figurative language or the pleasures of self-expression, can be found elsewhere, in music, in prose, in movies, in video games, in all the other ways in which we satisfy our desire for creating and consuming art in general? Why should one read poetry for knowledge instead of prose? Why should one read poems for pleasure when they could listen to songs, or watch movies? I’m not capable of answering such questions yet, either to a general reader’s or my own satisfaction, although I intend to give it thought.

Defenses of poetry are anyway numerous and the reader has no shortage of them to seek out. Dana Gioia, Matthew Zapruder, Seamus Heaney, Billy Collins. Many have taken a stab at propounding on the power of poetry and inspiring a love for it. Gioia’s new collection of essays, Poetry as Enchantment (Paul Dry Books, 2024), is an excellent place to start, if the reader is so inclined to hear wisdom from a lifetime’s worth of experience with the craft. Plenty of anthologies exist, too, popular and obscure, that showcase the best poetry has to offer. One can be made to appreciate and feel the importance of it by reading such things.

I’m interested, rather, in a categorical question. What does poetry do differently than all other artforms? Is there something of value to practicing the craft as poetry, and is there something we can gain by reading poetry that can be gained no other way?

What is Poetry?

The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur remarked that “the poet, in effect, is that artisan who sustains and shapes imagery using no means other than language.”2

Whatever poetry’s value, and however we choose to define poetry (a contentious topic nowadays), we can reasonably begin from the premise that poetry involves the use of poetic language. The poet uses language in such a way that he elicits in our imagination feelings, imagery, ideas, etc. Even the most unpoetic, the most literal poetry, when presented as poetry, insinuates to the reader that the words should be understood poetically. The English philosopher Owen Barfield lays it out simply:

When words are selected and arranged in such a way that their meaning either arouses, or is obviously intended to arouse, aesthetic imagination, the result may be described as poetic diction.3

I’ve spoken elsewhere about the kind of language poetry uses, and how it differs from everyday speech. The important thing to keep in mind is that poetry makes use of poetic language, and that the aim of such language is the shaping and sustaining of figures. The work of the poet, then, is undertaken in the imagination. It takes place in the realm of thought, imagery, impressions—where consciousness makes contact with the world.4 Poetry acts upon the imagination with poetic language.

This is to say nothing surprising about poetry, or art for that matter, as all art acts on the imagination. All art originates in the imagination, too. But poetry acts on the imagination, as Ricoeur said, “using no means other than language.”

You can remember this the next time someone attempts to tell you what poetry is. They will undoubtedly employ poetic language to do so. What they are trying to do is shape and sustain an idea of poetry in your mind, such that it seems clear to you what it is. It may or may not be true, but nonetheless it might give you an idea of it.5

If this also sounds like what politicians or advertisers try to do, that’s because rhetoric and poetry are cousins. Or they live in the same neighborhood. Whichever metaphor helps you picture things.6

But just as you don’t have to be a politician or advertiser to use rhetoric, you don’t have to write poetry to use poetic language. Such language pervades everywhere that a need for language arises.7 We use figurative language all the time, and any writer in any genre can use metaphors and write poetically.

This brings us back to the question of exclusivity. Is there something that poetry proper does differently that makes it worthwhile as a writer to practice, and as a reader to read?

Genre Conventions

Poetry is a genre of writing like any other, and genres are known by their conventions. If we are to understand what poetry does differently from other arts, we might ask ourselves what its conventions are, and if any of them are unique to poetry as such.

We’ve already noted that poetry makes use of poetic language. It uses figuration, figures of sound and figures of thought, and rhetorical devices8 to shape the imagination. Sometimes it uses lines and stanzas, rhyming, imagery, irony, symbolism, etc. The reader is probably familiar with many poetic elements. They are conventions of poetry, although neither one of them is exclusive to poetry as such, nor does a poem have to employ all of them, or any, to be a poem.

It is rather ‘the way’ in which these elements are used that differentiates poetry from other arts. A convention, after all, implies not only usage, but ‘a way of doing things.’

From the Latin convenire, meaning ‘to unite’ or ‘to come together,’ conventions are conventionally understood as a norm or standard or ‘a way’ of doing. This ‘way’ is interesting, as the word, in its original sense, involves movement and unity of purpose. Venire, “to come,” and con/com, “together.” Conventions aren’t rules only, such that you or I could, by a series of definitions, clearly establish the boundaries of a genre. We could not list off all the elements that make up a genre and say, whatever includes all these elements must be a part of that genre. We’ve all read poems that didn’t sound like poems, and we’ve all been struck by what we did not at first think was poetry, but turned out to be. It’s not only the use of poetic elements that makes something poetry, but that they’re used ‘in such a way’ that we recognize it as poetry. This sense of a convention is comprehensive and implies an understanding of a genre’s intentions or aims as a whole.

For example: a common genre debate is whether or not Star Wars falls into science-fiction or fantasy. Many would say that Star Wars is obviously science-fiction. It takes place in space. There are aliens and spaceships and exotic planets and futuristic technology. But others might object to this and point out that, while it does have many of the paraphernalia associated with science-fiction, it’s actually better understood as fantasy, for while it takes place in space, it happened “A long, long time ago,” as if in a mythical past. And while there are spaceships and laser swords, the function of that technology is much more similar to magic as it’s used in fantasy than, say, to the warp core in Star Trek, which the writers took great pains to explain the mechanics of, in order to convince viewers of its plausibility. Star Wars (pre-Disney) draws on tropes more commonly associated with fantasy, mythological tropes such as the struggle of good against evil, and the journey of the archetypal hero, whereas Star Trek deals with the social and ethical dilemmas of technology and interplanetary relations as it effects real people. The way in which they use their elements, and not the elements themselves, tell us about the genre convention that guides the storytelling.

Another good example is the opposing fantasy genres that Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones represent. One is high, the other low. One is mythological, the other is gritty and interested in realpolitik. These ideas have been articulated better by others.9 The point is to illustrate that the elements of a genre alone are not sufficient to understand its conventions. Rather, it must be taken into account the way in which an artist goes about using them. A convention broadly conceived gestures at a telos, a way of telling, and reveals itself by the unfolding of its story. A ‘way,’ after all, is a path, and one can only understand a path by walking it.

Poetry Properly Conceived

This convention, this ‘way of doing things’ in poetry, is hard to get a handle on. It resists being confined to propositions about it. This is because the artist always makes their own way, and every artist’s way is different, although it might be said they followed more or less the same path.

The 20th century modernist poet Wallace Stevens came to a similar conclusion. The essential convention of poetry he called “nobility,” although he took pains to make clear that such a thing was ultimately beyond definition.

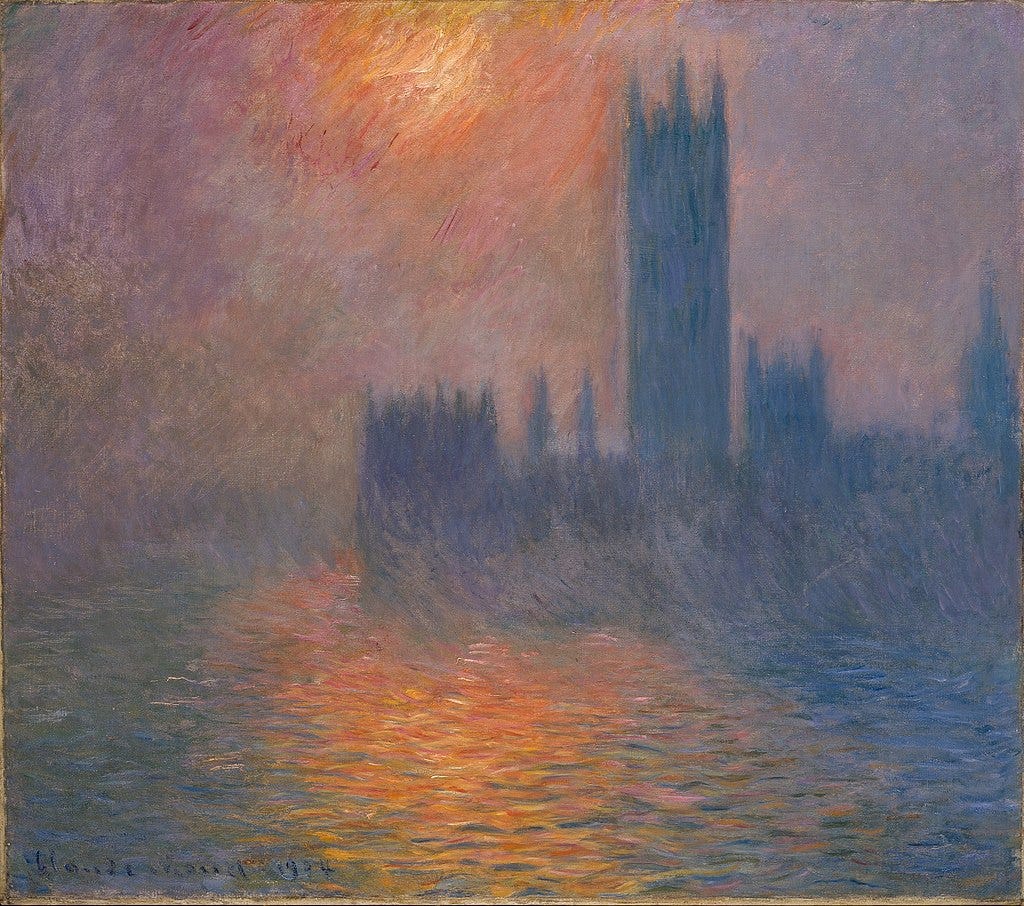

Yet the imagination gives to everything that it touches a peculiarity, and it seems to me that the peculiarity of the imagination is nobility, of which there are many degrees. This inherent nobility is the natural source of another, which our extremely headstrong generation regards as false and decadent. I mean that nobility which is our spiritual height and depth; and while I know how difficult it is to express, nevertheless I am bound to give a sense of it. Nothing could be more evasive and inaccessible. Nothing distorts itself and seeks disguise more quickly. There is a shame of disclosing it and in its definite presentations a horror of it. But there it is. The fact that it is there is what makes it possible to invite to the reading and writing of poetry men of intelligence and desire for life. I am not thinking of the ethical or the sonorous or at all of the manner of it. The manner of it is, in fact, its difficulty, which each man must feel each day differently, for himself. I am not thinking of the solemn, the portentous or demoded. On the other hand, I am evading a definition. If it is defined, it will be fixed and it must not be fixed. As in the case of an external thing, nobility resolves itself into an enormous number of vibrations, movements, changes. To fix it is to put an end to it. Let me show it to you unfixed.10

As Shakespeare’s Kent declares to Oswald, “I’ll teach you differences”,11 so Stevens describes the kind of nobility associated with the poet by negating everything surrounding it. It is a spiritual height and depth which the poet is capable of reaching in poetry. A nobility that must remain unfixed, but a nobility which it is the poet’s business “to overhear and to record.”

For the sensitive poet, conscious of negations, nothing is more difficult than the affirmations of nobility and yet there is nothing that he requires of himself more persistently, since in them and in their kind, alone, are to be found those sanctions that are the reasons for his being and for that occasional ecstasy, or ecstatic freedom of the mind, which is his special privilege.

It is such nobility that echoes throughout the poetic tradition. It is the kind of voice that originated in the old epics, in the heroics of Gilgamesh and Enkidu, Achilles and Odysseus, Rama and Hanuman, Beowulf and Hrothgar. It’s in the Mahabharata and the Shahnameh, in the Aeneid and the Poetic Edda. But it also equally existed in the smaller lyrics of Alcman and Sappho, and in the courtly love poetry of India and China. It existed in the qasidas of pre-Islamic arabs, and the tanka of the Heian poets. It existed in the spiritual ecstasy of the Sufis and the visions of Dante. It’s in the vitality of the personalities of Chaucer and Shakespeare. It’s in the high imagination of the Romantics, the yawpings of Whitman, the cool sobriety of the Modernists. It is, in short, an elevation and deepening of the imagination by means of poetic language.

Stevens, drawing upon Shelley, elaborates elsewhere:

Although there is no definition of poetry, there are impressions, approximations. Shelley gives us an approximation when he gives us a definition in what he calls “a general sense.” He speaks of poetry as created by “that imperial faculty whose throne is curtained within the invisible nature of man.” He says that a poem is the very image of life expressed in its eternal truth. It is “indeed something divine. It is at once the centre and circumference of knowledge…the record of the best and happiest moments of the happiest and best minds…it arrests the vanishing apparitions which haunt the interlunations of life.” In spite of the absence of a definition and in spite of the impressions and approximations we are never at a loss to recognize poetry.12

Lofty to be sure. But isn’t it precisely in poetry that we are granted such loftiness? Where else can one hear a voice like Keats’ in “The Eve of St. Agnes,” or like Crane’s in The Bridge? Where else do we suspend our disbelief for the magnanimous voice of The Duino Elegies or “The Song of Myself”? Where else do we still accept such claims upon truth and beauty and wisdom except in poetry? I think that’s Stevens’ point. The same way in fantasy movies we expect a certain amount of pseudo-archaic dialogue, or in romances we expect lovers to end up together—and we expect these things because it is their convention, their ‘way’ of telling—so in poetry we expect a certain nobility of the mind that augments our own imagination. And I do not think it is to be found anywhere else, in any other art that uses language. It is a certain way of speaking about things, a way of figuring that is ennobling.

Yet Stevens admits that such nobility is “conspicuously absent from contemporary poetry.” The sentiment, fifty years on, can still be felt.13

At the end of his first essay in The Necessary Angel, Stevens further clarifies that the nobility he is speaking of is not an artifice invented by the poet, but rather a characteristic of human nature that is embodied in him.

It is not an artifice that the mind has added to human nature. The mind has added nothing to human nature. It is a violence from within that protects us from a violence without. It is the imagination pressing back against the pressure of reality.

Not a fanciful nobility, but a real force of human nature. An imagination with “the strength of reality.”14 This, to my thinking, gets closest to a meaningful conception of poetry. It is something within the poetic tradition that seems exclusive to it. It is, at any rate, what brings me back to the greatest poems. I read them and feel myself more noble, more courageous, more capable. Their imagination, noble in its conception, becomes a light in my own.

What exactly this voice is is hard to speak about. It’s easier to say what it’s not than try to fix it into place and risk losing its essence. It’s not, as Stevens points out, a solemnness or a sonorousness or a moralizing. Or, rather, it’s not only these things. Consider the question for yourself: what brings you back to poetry? What are you searching for when you read a poem? Is it not a way of speaking about things? Is it not a way of looking at things that illuminates consciousness and makes the world shimmer? And where else do you go looking for such a thing? What does it better than poetry?

Those who can’t remember nursery rhymes, or don’t have an ear for figurative language or analogical thinking, are, unfortunately, beyond the pale of our help.

Ricoeur, Paul. The Rule of Metaphor. Routledge Classics, 2003.

Barfield, Owen. Poetic Diction. Wesleyan University Press, 1973.

The English philosopher R. G. Collingwood, following Kant, said of the imagination that it’s an intermediate level of experience where the purely psychical (sensory) meets the intellect (conceptual).

Unless they say “Poetry is anything” or “Anything can be a poem,” in which case you won’t have any idea what poetry is. The people who say these things are, unsurprisingly, not poets, or not very good ones.

In A Rhetoric of Motives, the American philosopher Kenneth Burke defines rhetoric as “the use of words by human agents to form attitudes or to induce actions in other human agents.” The essential difference between rhetoric and poetry is a confounding one, as it’s the aim of both to ‘form’ something in the mind. In my personal opinion, pure poetry is only concerned with ‘showing,’ while rhetoric is concerned with ‘doing.’

All language is poetic, in the sense that all words have their origins in images, in a figuring of reality in the imagination. At the moment I can’t remember where this idea comes from.

Richard Lanham’s A Handlist of Rhetorical Terms is a good reference book for these devices.

See Mike and Jay of Red Letter Media, and many a film essayist on YouTube.

Stevens, Wallace. “The Noble Rider and the Sound of Words.” The Necessary Angel. Vintage Books. 1951.

King Lear. I.iv.

Stevens, Wallace. “The Figure of the Youth as Virile Poet.” The Necessary Angel. Vintage Books. 1951.

I find much of poetry today to be the opposite of noble. It does not elevate but lower, or else it elevates by false pretense or mawkishness. It strips bare and lays raw. It reduces and obfuscates. It dismantles and deconstructs. It goes for cheap shocks and emotional grifts.

Stevens, Wallace. “The Noble Rider and the Sound of Words.” The Necessary Angel. Vintage Books. 1951.

Loved this! It split me in two. Half of me (the “noble” half) joins Stevens in shaking a fist at the bastardisation of an artform rooted in divine impulse (“that imperial faculty” as Shelley so beautifully puts it).

The other half wants to defend the absence of nobility in modern poetry. The world has been secularised to a pulp and our poetic language along with it. When Bukowski (whose intentions were anything but noble) wrote “bullshit is bullshit and that’s all it is”, did the words cease to be poetry? I think what defined them were simply his putting pen to paper and saying “this is a poem”. Much in the same way Duchamp’s urinal had as much a claim to be art as anything in the Louvre. Perhaps Bukowksi and Duchamp’s divine impulse was telling us to get our noble heads out of our arses. (Disclaimer: I can’t stand Bukowski.)

Defending his decision to write Jerusalem in free verse, Blake wrote: “Poetry Fetter’d Fetters the Human Race.”

There is something SO special about poetry. Now, I adore fiction (novels, plays, novellas, short stories, etc), but the distilling of language (as in a poem) is like putting the star at the top of the Christmas Tree.