I watched The Return (2024) last week, a retelling of the homecoming of Odysseus, starring Ralph Fiennes and Juliette Binoche. I wasn’t moved by Odysseus and Penelope’s relationship, which I took to be the crux of the film, so overall it seemed unsuccessful in its aims. I wrote about what I believed was missing from their characters, that ideal called homophrosyne, or “like-mindedness,” here.

But I would suggest seeing it purely on the basis that I generally support independent films like this, which don’t get made nearly enough. When’s the last time the industry has tried translating something like The Odyssey into film? One of the great works of literature. I give the director Uberto Pasolini immense credit for such ambition and for his approach to the story which was unique and singular in its vision. I would always rather watch an attempt at greatness than one of the many inevitable films that gets made every year. It’s worth seeing in theaters just so we get to see more of them.

About midway through the film, Odysseus is reunited with his son, Telemachus, whom the evil suitors have been keen to get rid of. Antinous, the head suitor for Penelope’s hand, has threatened to kill her son if she doesn’t choose him as her husband. Apparently Antinous is the sole reason the other suitors haven’t already killed the boy, but his patience is at an end. Even before Penelope can make a decision, Antinous and the other suitors leave the palace grounds to look for Telemachus.

They find him at the house of Eumaeus, where Odysseus is staying. The veteran king dispatches two of the suitors with brutal efficiency, and when the others arrive, they chase Odysseus and Telemachus through the island’s sultry forest.

Through junipers and pine, over the gnarled roots of olive trees and up steps of limestone cliffs they race. Odysseus trips at one point, and we worry if he’s lost a step in his old age. Will he make it away in time before the suitors catch him and realize the king of Ithaca has returned?

Eventually the heroes reach a grotto and, swimming to the other side, climb up the back of a waterfall and escape their pursuers. The suitors, with their sleek-headed hunting dogs, have lost the trail, and give up for now with their plan to murder the prince.

As chase scenes go, it’s not a particularly thrilling one. It’s not Tom Cruise running through the streets of Shanghai in Mission: Impossible III. The score is good, the editing is quick, but the actors seem slow and clumsy-footed, probably because of the uneven terrain of the island. It’s not very a good place to have a chase scene. Nor does it seem like the kind of movie that needs a chase scene, as it’s otherwise a slow, meditative arthouse flick about violence and estrangement (actually, it probably does need a chase scene).

None of this is in the poem, by the way. Odysseus never kills two suitors at the house of Eumaeus, nor does he escape into the forest with Telemachus. But neither is this a criticism of the film. I’m not a purist. I don’t care if the movie is faithful to the source material or not, unless that happens to be part of its aim. What matters is whether or not the film succeeds as a film.

This wasn’t always the case. Back when Troy (2004) came out I was a sophomore in high school and I’d just finished The Iliad. I remember being upset by the movie because they killed Menelaus and Menelaus wasn’t supposed to die in the fight with Paris. And they killed Ajax and Ajax wasn’t supposed to die to Hector. And the war was supposed to take 10 years and it happened in weeks. And there were no gods in it. And they all had British accents. I was appalled at the sacrilege. I went around smugly telling everyone “the book was way better.”

That was before I’d really gotten into movies and understood that they have their own conventions, their own grammars, for storytelling. Now I actually like Troy. I think it’s perhaps the last great swords-and-sandals flick. The British accents are actually part of its charm. The star-studded cast (Brad Pitt as Achilles, Sean Bean as Odysseus, Brian Cox as Agamemnon!) I used to find obnoxious, now I think it’s perfectly in keeping with the tradition of films going back to Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra and Charlton Heston’s Ben-Hur. I like the grandstanding monologues and the slo-mo shots where the hero falls and there’s non-diegetic, high-pitched chanting to dramatize it. And the fight between Achilles and Hector is one of the more iconic movie fight scenes that still gets shared on social media consistently.

What matters for me now is whether or not a movie succeeds as a movie. That means that I judge it according to the conventions of its genre, according to whether or not it successfully fulfills or subverts the expectations set by its conventions. Troy, though it fails as an adaptation, succeeds as a film. The Return fails as an adaptation, yet only sometimes succeeds as a film. It does have beautiful shots, clever match cuts, and occasional poignant lines delivered by seasoned leads. But its pacing lags, its plotting is contrived, the motivations of its characters are often unclear, and its chase scene is bad.

On Some Conventions of Film

It’s understandable that Pasolini would include a chase scene in his movie where none exists in the original. It occurs late in the second act, and by that time the story beats have begun to feel a bit repetitive. Odysseus has returned but he’s war-torn and sea-weary. Penelope has to choose a suitor but the suitors are all brutes so she delays. She has standoffs with them, and with her son, and her son has standoffs with them, and they terrorize the island, and all while Odysseus wavers. The movie has told us all of this in the first act, and the conflict is merely repeated in the second until the chase scene happens. When it happens, it finally feels like something has happened, like the story is finally going somewhere. This is exactly what a chase scene is meant to do.

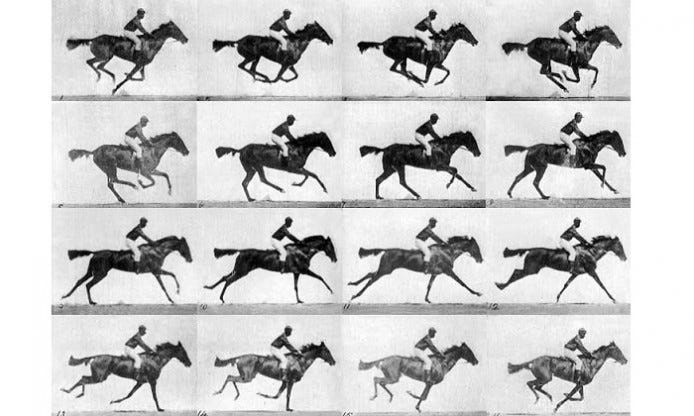

Chase scenes are part of the language of cinema. They’re an expression of an essential characteristic of the medium itself: movement. Going back to the very first footage, the Lumière brothers' “L'arrivée d'un train à La Ciotat” or the successive stills of Muybridge’s “Horse in Motion,” movement is at the heart of cinema. It makes sense that Pasolini would include a chase scene rather than, say, all the talking that goes on in Homer’s poem. Although he clearly appreciates the poem, and pays homage to it by including references and details that a fan of the book would pick up on, he also understands that he’s making a movie, and movies have a different set of conventions.

Movies are about image and movement. They’re a visual art. This is an obvious point to make, but it’s worth considering how the medium of an art expresses itself through its conventions, in order to be able to evaluate that art properly.

A convention, I discussed in a previous post, is a “way” of doing something. It’s how the artist takes up their subject and tells a story. That way is a path laid out by the tradition of the art, wherein choices have been made according to the medium of the artform. Each choice is a response to an inherited set of conventions that either subverts or fulfills the expectations of those conventions. The patterns that emerge across these choices, or ways of doing, create a vocabulary, a grammar, which forms the relationship between art, artist, and audience.

For example, a common film grammar is the way progress in a story is depicted as movement from screen left to screen right. Picture the fellowship in The Lord of the Rings racing across the mountain ranges of Middle Earth.

The screen direction is left to right. This kind of movement is common in movies, and it means something to the artist and the audience. The characters are on their journey, they move left to right, progressing forward, and they move backwards to suggest the opposite. They can also move into the camera or away from it; this movement, too, implies.

Screen left to screen right implies progression of the plot. It suggests advancement. And going screen left or screen right can visually convey a character’s decision in a film, as explained by the YouTube film essay channel Every Frame a Painting.

Take, for example, the image from The Return I showed earlier, where Odysseus strikes and kills two of the suitors.

He faces screen left. He faces backwards to strike at the suitors, because, in Pasolini’s Odyssey, Odysseus is traumatized by war and wandering. Up until this point in the film it’s clear he’s wary of returning to his old, violent ways. He’s pained by what he’s done to get back home. The tension in the scene comes from our wondering what he’ll do. We’re wondering whether he’s actually been defeated by war, or if he’s just been lying low and waiting for the right moment to reclaim his kingdom.

He faces screen left in this terrific shot as if to turn back and strike down, not only the suitors, but the ghosts of his past that are behind him. He’s facing backwards, which implies a “facing down of his past.” The staging is intentional, and intelligible, because screen direction is part of the grammar of cinema. It’s also obvious to anyone following the plot that this is the moment where something changes in Odysseus. After it he becomes the man of action again, and the scene ends with a beautiful shot of the blood of the suitors mixing with the soil.1

But this is partly why the chase scene that follows feels dull and unnecessary. Nothing is gained by it. It’s not thrilling in its own right as a chase scene, because the terrain is too uneven and none of the actors are good runners; and it’s much less thrilling than the scene that preceded it.2

By facing screen left, I think Pasolini also wanted to suggest a regression in Odysseus’s character and his return to violence, as there seems to be a critique, a condemnation, of violence of any kind in the film. The massacre of the suitors, in another example, is thoroughly “deglamorized.” Whereas in Homer it’s a culmination, a heroic triumph, in Pasolini’s film it’s done without fanfare or satisfaction. Odysseus stands above the sunken floor of the dining hall and picks them off one by one with his bow. He drains his quiver methodically and without passion, as a farmer in the midwest picks off invasive prairie dogs as a matter of upkeep. Penelope watches the beginning of it, then runs into the other room with Eurycleia to lament the slaughter in her house. She returns to watch Odysseus and Telemachus finish off Antinous, shrieking as her son lands the final blow. Penelope has become a witness to the horrors that traumatized Odysseus. She overlooks his carnage in the sunken dining hall, and finds him standing there, bewildered, like a lost puppy.

This becomes a necessary step in the reconciliation and reunion of Odysseus and Penelope. She’s seen something of what he’s seen, and together they can begin to heal. She says as much in the final scene of the film when she bathes him.3

“We’ll remember, and forget, together.”

It’s the best scene in the film. The camera peaks behind their intimacy to a window overlooking the Mediterranean, and slowly pushed out to the searing sea, where a single ship balances on the horizon.

A Poetic Ending

Homer ends Odysseus’s journey not with Penelope but Laertes, his father, in a decidedly uncinematic ending. Odysseus, in disguise, plays with Laertes, insulting him and making up a story about meeting his son, before he reveals himself. They have a moment together, but then some relatives of the suitors gather, and a potential conflict between the families of the island almost breaks out before the gods end the fighting and peace is restored.

Of course you wouldn’t include any of this in a film adaptation. You technically could. There’s nothing stopping a director from doing it. It just isn’t done. It isn’t the way stories get told in cinema. It isn’t part of the grammar. That Odysseus would mess with his father after everything he’s gone through would undercut the emotional resolution of the film. And though it makes sense that the families of the suitors would rightly be upset, and might seek retribution, to introduce a new conflict at the very end of a story, to try and reestablish tension again, only to quickly resolve it, would surely ruin the sense of closure in any film.

In The Return of the King, Peter Jackson cut out the Scouring of the Shire, the penultimate chapter of the book, where the hobbits return from their quest to destroy the One Ring, only to find the shire has been taken over by Saruman. They have to raise a rebellion among the townsfolk to take back their home. As far as cinema is concerned, such a scene is considered anticlimactic (it’s even called this in the Wikipedia article). But this is to judge the book by the conventions of film. In the literary tradition which Lord of the Rings and the Odyssey are a part of, returning home and reestablishing order is part of the journey. It’s not enough that Frodo has destroyed the One Ring; he must return home with the wisdom he’s gained on his quest, and use it to save his people. Likewise, it’s not enough that Odysseus has reunited with his wife and father, or even that he’s killed the suitors who’ve been plaguing his house. He has to restore order to his kingdom of Ithaca before the story can be resolved.

Each art abides by its own conventions, and must be understood within the context of those conventions. I was going to use this discussion of film conventions to talk about the conventions of poetry, but it seems like this has actually turned into a review of The Return, so I’ll save it for the next post. Till then.

He does kill someone before this, during a scene where he gets beat up by the suitors, but the killing is entirely accidental. The whole scene itself felt unnecessary.

Why not have a scene where Odysseus establishes a relationship with his estranged son, and together they plan to take back the palace? Pasolini isn’t interested very much in Telemachus or his relationship with his father. I don’t think they actually have a conversation the entire movie.

This is something I appreciated that Pasolini changed from Homer. It’s not the maids who bath him, it’s Penelope herself. The act is clearly much more significant if she does it.

This is great. I didn't realize Every Frame a Painting was active again, but I looked it up after you mentioned it. Great channel!

The ability to bring Muybridge into a film review has utterly sprung me. Bravo!