Brutus The Senator

You were quite officious, Cicero, in your refusal to grant the titles I wrote you of. You dislike the men I surround myself with because they’re gainful. Do you believe you go through the streets of the Republic of Plato and do not dirty your shoes in the scum of the city of Romulus? Remember that our friend Cato, with the best of intentions and the most absolute honesty, often does harm to the State. I wrote to you, not him, because I thought you the more reasonable. Yet now you deny Scaptius the prefect. Why? He roughed up some chieftains at Cyprus? What do you care about the Salaminians? Have you a bleeding heart for provincials and not your fellow Romans? Scaptius is my man. He knows how to collect, and can, when he must, persuade them of what’s best. He must be given an office within the month. Do not pretend you are like Cato, my friend. It would be like the moon bragging of its light so that the people noticed all its blemishes. Your integrity is but pale imitation, for he competes with the fervent in virtue, the restrained in moderation. He is blameless among the most abstinent. But none believes even half of that about you! Exactly this sort of chasing after morals is losing us the people’s will to Caesar. Cato will not bribe, but he bribes lavishly, the plebs with grain, the nobles with tax breaks. Unscrupulous in his pity and generosity. The old clement master, Cassius calls him. Therefore, it’s worthless to you either way, either to appear principled or to act so. As if we didn’t know the course of your career and how you took the fairest winds to steer it in your favor. As if the Senate did not know why you persecuted Hybrida, not because of his abuse of Macedonians but because it was, by your calculation, an easy win. It’s plain to anyone with eyes to see. New men like you are always hungry. Eager for the chance to chase prestige. You overtake the pack, but we, in shade, with noble names, watch you in the open, and note your strengths and shortcomings. We all know your weakness is your vanity. It spoils the river of rhetoric that spews from your tongue as the Tiber is sullied as it passes the slums. It contaminates your tired exordia on justice and mercy. Who are you to censure my interest rates? I will charge the provinces what is fair according to Rome’s interests, not theirs. I hope you will see my side of things hence, for the sake of our City. I’d rather you be a bridge at times than an impediment. There are more pressing matters presently. As I write, Pompey and Caesar are at odds. One must give way, but neither will concede. They may come to blows like earthquaking gods. But I must cut my letter short, and go. They’ve finished filling up the new pond I had commissioned for my estate. The bearded mullet have just come in, and I mustn’t make the handlers wait.

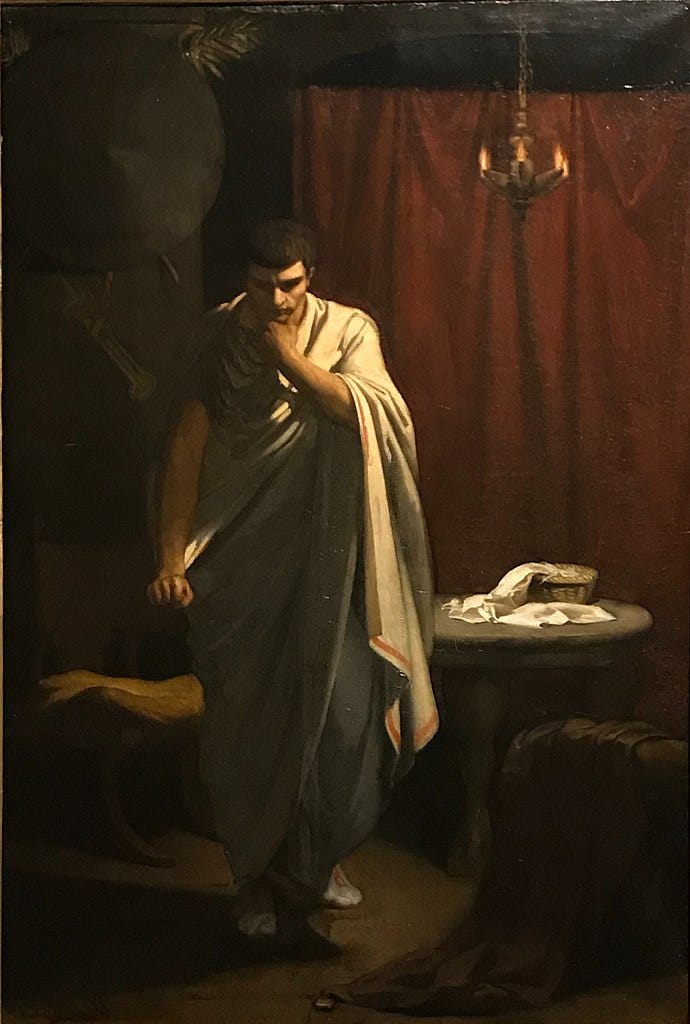

If you know of Brutus, you probably know him as “Noble Brutus.” He is an invention of Shakespeare’s (as so much in our imagination turns out to be). He is the man who stands up to the tyranny of Caesar for the good of Rome. He personifies that essential Roman virtue pietas, the strong sense of duty one feels towards one’s country and one’s gods. He is honor bound to his state. He is the man who says to Cassius

Set honor in one eye and death i’ th’ other,

And I will look on both indifferently;

For let the gods so speed me, as I love

The name of honor more than I fear death.

He means it too, and will fall on his sword to preserve his honor and restore his sullied conscience. He is a virtuous man whose only flaw, according to Harold Goddard, is that he knows he’s virtuous.

And there lies the tragedy, for a man should have no more acquaintance with his virtue than a woman with her beauty.1

He is perhaps too aware of just how much of an impact his honor has to sway the people of Rome. He is too aware of how much his nobility is worth.

The word “nobility” originally referred not to the quality of one’s moral behavior but to their breeding. Of course back then these were assumed to be the same thing. One was a good person by virtue of being born noble.

Brutus was “noble” in one sense because he was descended from Junius Brutus, the man who kicked out the last king of Rome, the man who ended monarchy and ushered in the freedom of the Republic. He is “noble” in another sense in Shakespeare’s play because he chooses to embody those values of his ancestors that liberated his people from the tyranny of rapacious kings. Believing he was fulfilling the obligations required of him by his country, he joins the conspiracy to kill Caesar, in the name of preserving liberty. And though he might have been doing the right thing,2 because he was blinded by vanity he goes about it the wrong way, and ultimately fails in his duty to his country and to his friend.3

In the dramatic monologue above, however, Brutus is “merely” noble. He is a patrician, and therefore of that class of noblemen, but he has yet to distinguish the noble from the merely noble.

The Brutus of the poem comes partly from Plutarch (where Shakespeare’s comes from) and partly from Cicero’s letters.4

Cicero, writing to his friend Atticus, complains of Brutus’s unscrupulous behavior in recovering debts among the provincial territories. Apparently he charges exorbitant interest rates (48%) while the standard was 12%. Cicero is reluctant to grant the title of prefect to one of his men, Scaptius, because Scaptius, acting on Brutus’s behalf, had recently besieged the locals of Cyprus, starving five of their senators to death, in an attempt to recover funds. Moreover, Cicero has a problem with the tone Brutus often seems to take with him.

However, I have granted all this in favour of Brutus, who writes very kind letters to you about me, but to me my-self, even when he has a favour to ask, writes usually in a tone of hauteur, arrogance, and offensive superiority.5

What emerges for me of Brutus’s character is a man, like Shakespeare’s, who is too close to his nobility, too comfortable in the assurances of his nobility. But it is a nobility, not of character, but merely of birth and lineage. He feels he is a native Roman. Romanness is something you’re born with. It’s in the blood. And so he has no qualms with taking advantage of what is essentially Rome’s property, her provinces. These are her subjects, he thinks, for they are not real Romans.

I got this sense of Brutus also from a curious passage in Plutarch’s Lives, where Plutarch is distinguishing between the way Brutus writes in Latin to his fellow Romans versus in Greek to the subjects in Asia Minor he exerts authority over.

In Latin, he had by exercise attained a sufficient skill to be able to make public addresses and to plead a cause; but in Greek, he must be noted for affecting the sententious and short Laconic way of speaking in sundry passages of his epistles; as when, in the beginning of the war, he wrote thus to the Pergamenians: “I hear you have given Dollabella money; if willingly, you must own you have injured me; if unwillingly, show it by giving willingly to me.” And another time to the Samians: “Your counsels are remiss and your performances slow; what think ye will be the end?” And of the Patareans thus: “The Xanthians, suspecting my kindness, have made their country the grave of their despair; the Patareans, trusting themselves to me, enjoy in all points their former liberty; it is in your power to choose the judgment of the Patareans on the pretence of the Xanthians.” And this is the style for which some of his letters are to be noted.6

I think what Plutarch is mistaking as an affected writing style is actually a tone of voice toward certain parts of the world, and certain peoples, who are not, in his eyes, true Romans. This kind of disdain comes from overvaluing, and resting on, the nobility of your pedigree.

In addition, Brutus, at this point, is someone who has functionally retired to the countryside, and plays a part in Roman politics in title only. The letter by Cicero is dated around 50 BC, which is two years before civil war officially breaks out between Caesar and Pompey.7 Before that, Brutus is living comfortably abroad and on his estate outside Rome, as many senators did. Happy to enjoy the benefits their nobility bestowed while forsaking its many responsibilities. It was precisely this kind of attitude Cicero believed would lead to the downfall of Rome.

And since our leading men think themselves in a paradise if there are bearded mullets in their fish-ponds that will come to hand for food…

Their nobility, thoroughly decadent and apathic at this point, is devoid of pietas, neglectful of the obligations placed upon them to ensure a functioning state. That neglect would open the way for a man like Caesar to swoop in and save the city from itself…

Thank you for reading

Some other poems in the series so far:

“The Cult of Caesar” - On the divine status of Julius Caesar

“The Ritual Sacrifice of Caesar” - On Caesar’s assassination

“Caesar Ultor” - Caesar takes bloody revenge for his murder

“Caesar Triumphator” - As a god, ruminating on the order he’s created

“Capo the Aquari” - On getting by in the Empire

“The Sibyl Hands Superbus the Books” - The voice of the Sibyl casts a warning

“SPQR” - on the bodies of the State

“Civitas” - On the sentiments of the optimates and the populares

“Vixerunt” - On the fate of the Catiline conspirators

“The Coming of Caesar” - Heroic, galloping dactyls on the omens foreboding Caesar

“Populus” - On Caesar’s political victory over Cato

“Res Publica” - On the decay of the State

“Veni Vidi Vici” - On Caesar’s 10+ years of military ascension

The Meaning of Shakespeare, Volume 1. pp 311

For our Julius Caesar unit, my students must put on a mock trial arguing for and against the justness of Caesar’s murder.

As he falls on his sword, his final words are telling. “Caesar, now be still; / I killed not thee with half so good a will.”

ibid.

Plutarch’s Lives Vol II. The Modern Library Edition. pp. 573.

At which point many senators and noblemen would be forced to pick sides and take up arms, which Brutus certainly does, joining Pompey and fighting in the battle of Pharsalus. He is an aristocratic snob, but he does eventually put his mouth where his money is.

I think the nobility of Shakespeare's Brutus is more nuanced. He didn't, after all his fine words, fall on his sword. He got someone else to do it because he didn't have the nerve. He dithered. What was he condemning his family to? What was in store for Portia with him an avowed traitor? Cassius, despised and less than noble in Brutus's eyes, was the one with the courage to see the plot through to the end without faltering. I think Shakespeare makes him a much more sympathetic and noble-spirited character than Brutus.