Caesar Pater Patriae

A new way has been prepared out of the old.

The land shall be tilled and worked that for so long,

overgrazed and salted by greed, lay fallow.

We shall practice again obedience to the law,

wash clean our sins by the doing of our duty,

and by work’s benediction rejoice in austerity.

The temples, reopened, are restored to their former glory.

Pay your respects with incense and offerings to the gods.

We shall return to the ways of our ancestors before long.

The streets are safe. The Lares guard the roads again.

You may conduct affairs with peace of mind, kept by

the urban cohorts, the nightwatch, and praetorians.

The young once more shall respect their elders.

Barred are boys from the Lupercal and bloodthirsty games.

And the virgins of Vesta once more made chaste.

Rome shall lavish the blessings of a just city

upon those who do greatest benefit to her.

We shall honor the family, and shame disgrace.

The oxen shall be yoked again and driven,

and the champing horse and stubborn ass,

and every beast of burden groan before their toil.

Until the land returns to us a richer soil,

until the harvest is once again our gain

and we fattened by fields of waving grain.This is the man, this one,

Of whom so often you have heard the promise,

Caesar Augustus, son of the deified,

Who shall bring once again an Age of Gold

To Latium, to the land where Saturn reigned

in early times.—Virgil1

In Book VI of The Aeneid, Aeneas goes to the underworld and is granted a vision of the glorious future of the city his descendants are to found. The poet affords himself such an opportunity to praise the living Caesar, to whom the book is dedicated and to whom, in 19 BC, he likely performed this very section.

By that time Augustus had already accomplished much in the way of reforming the City. He rooted out violence and quelled civil unrest. He purged a fat and lethargic Senate. He took a census in 28 BC. He returned the culture to the customs of the mos maiorum, the “ways of the ancestors.” He had become the archetype of the Patriarch, the one who makes order out of chaos, and in 2 BC he would be given the title Pater Patriae, “Father of the Fatherland,” in recognition of all that he’d done to save the City from itself. It was said of Augustus that he found Rome “a city of brick, and left it a city of marble.”

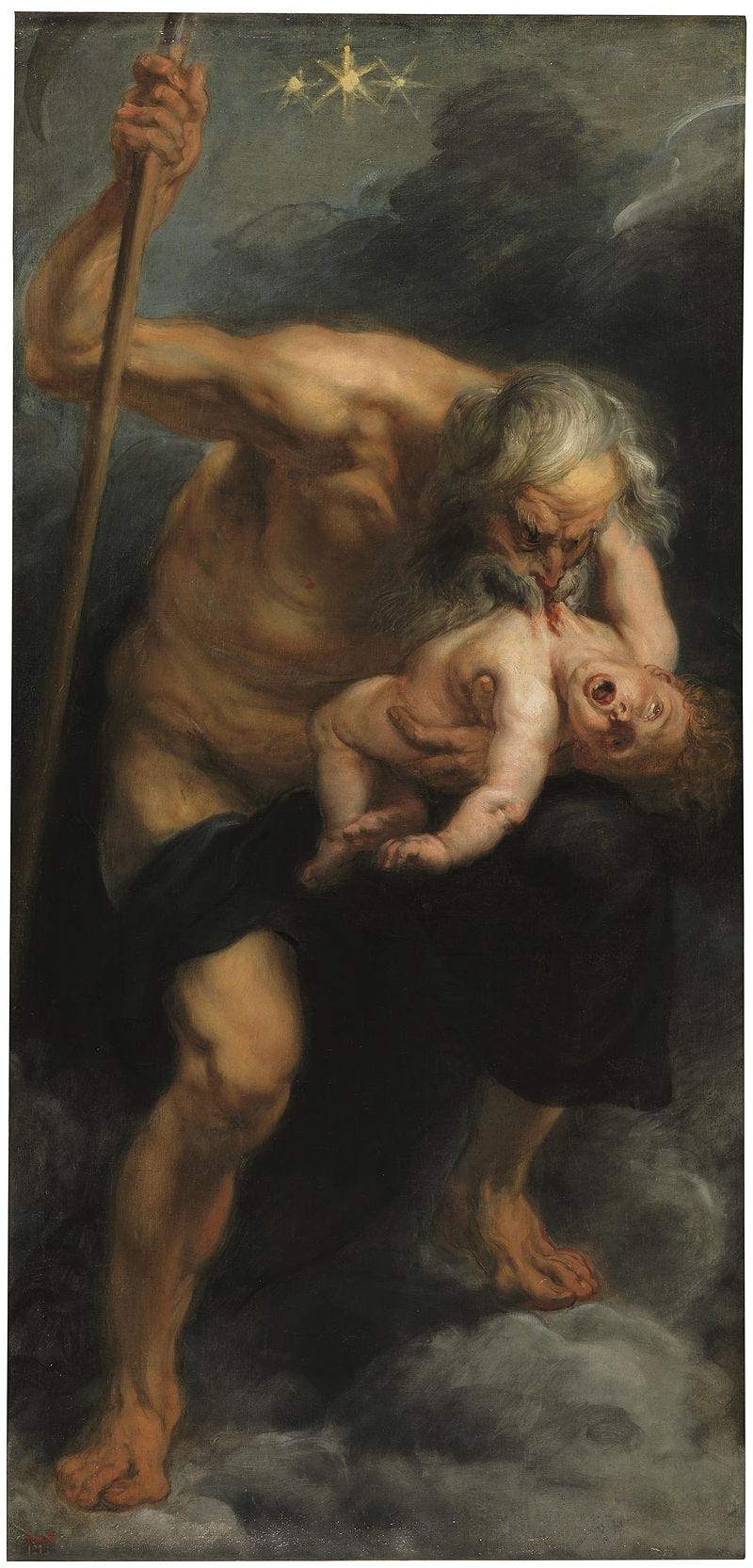

It’s no coincidence that Virgil, in the quote above, mentions Saturn. Today we tend to think of Saturn only as the mad god who, paranoid at his overthrow, devoured his own children. But the Romans were familiar with another side of Saturn. This Saturn ushered in his own Golden Age, as Virgil tells us in Book VIII.

These woodland places

Once were home of local fauns and nymphs

Together with a race of men that came

From tree trunks, from hard oak: they had no way

Of settled life, no arts of life, no skill

At yoking oxen, gathering provisions,

Practising husbandry, but got their food

From oaken boughs and wild game hunted down.

In that first time, out of Olympian heaven,

Saturn came here in flight from Jove in arms,

An exile from a kingdom lost; he brought

These unschooled men together from the hills

Where they were scattered, gave them laws, and chose

The name of Latium, from his latency

Or safe concealment in this countryside.

In his reign were the golden centuries

Men tell of still, so peacefully he ruled,

Till gradually a meaner, tarnished age

Came on with fever of war and lust of gain.

The Saturn of this passage is an Order-Maker, just as Augustus was in the eyes of Virgil. He brings the race of fauns and nymphs and tree men together and gives them laws. He teaches them skills that enrich their lives. The name Saturn comes from satus, “sowing,” according to Varro.2 He teaches them agriculture, the sowing and harvesting of grain, which evolves them from a hunter-gatherer society into a settled, agricultural one. He gives them the means to great wealth and abundance, and for this the Romans honored him at the Saturnalia, a grain and fertility festival, every December.

It’s this Saturn that Virgil compares Augustus to, and at the time the comparison must’ve seemed an accurate one.3 Caesar’s reforms really had brought order to a chaotic Republic, one which had, for several generations, succumbed to its vices, and could not bear the remedies for them. Corruption and decadence alienated the classes, and recourse to violence and civil war had become common since the days of Sulla. It was inevitable that such reforms would become necessary for the City to adopt if it were to survive at all.

Although Caesar himself was far from the examples which he intended his laws to set, at least in the beginning. His vengeance was rapacious. Suetonius says “he was not restrained in victory but sent the head of Brutus to Rome to be thrown at the foot of Caesar’s statue.”4 He wielded his newfound power like a princely tyrant.5

And though he reformed the culture around sex and marriage,6 as a young man he was known to bed other men’s wives, even taking them to his chambers in the middle of dinners he’d invited them too, while the husbands sat befuddled and impotent to stop him. It was joked that the patrician Tiberius Claudius Nero gave away his wife, Livia, “like a daughter” to Caesar when the two were married.7 The marriage itself took place only three days after Livia had given birth to Claudius’s second child. This was the same Caesar who would enact laws against adultery and promote the institution of marriage as a sacred one. He also, in private, fancied himself a god.

Yet, things being what they were, Rome herself desired reform more than she desired a good man to reform her. The times make the man, as they say, and the necessity of the situation obviated such preferences in the minds of the people. It has been argued that Augustus eventually became the man he desired his citizens to become.8

Yet just as the Golden Age of Saturn was “tarnished,” as Virgil says, “with fever of war and lust of gain,” so too would the Pax Romana of Augustus decay into constant wars of expansion and petty lusting after the powers of the throne. The lawgiving Saturn would once again become the power-hungry Saturn, the Saturn paranoid of usurpation, the Saturn who retaliates in advance and devours his own children.

Was Virgil, in comparing Augustus to Saturn, praising his prince’s newfound peace, or warning of the pitfalls to come? Such is the case with myths, that they often tell stories we either cannot understand or are helpless to prevent.

Thank you for reading

Some other poems in the series so far:

“The Cult of Caesar” - On the divine status of Julius Caesar

“The Ritual Sacrifice of Caesar” - On Caesar’s assassination

“Caesar Ultor” - Caesar takes bloody revenge for his murder

“Caesar Triumphator” - As a god, ruminating on the order he’s created

“Capo the Aquari” - On getting by in the Empire

“The Sibyl Hands Superbus the Books” - The voice of the Sibyl casts a warning

“SPQR” - on the bodies of the State

“Civitas” - On the sentiments of the optimates and the populares

“Vixerunt” - On the fate of the Catiline conspirators

“The Coming of Caesar” - Heroic, galloping dactyls on the omens foreboding Caesar

“Populus” - On Caesar’s political victory over Cato

“Res Publica” - On the decay of the State

“Veni Vidi Vici” - On Caesar’s 10+ years of military ascension

trans. by Robert Fitzgerald

De lingua latina

In retrospect it seems prophetic. More true than perhaps Virgil had anticipated.

“The Life of the Deified Augustus.” Lives of the Caesars. 13.

The word “prince” derives from the title he adopted, princeps, which meant “first” or “foremost,” and was used as a way to avoid calling himself a king.

These laws, the Lex Julia, were enacted in 18 BC, and promoted marriage, encouraged large families, and severely punished adultery. Augustus’s own daughter would be subject to such laws, and banished for a time for her promiscuity.

Claudius had narrowly avoided the proscriptions of Augustus, and was perhaps handing over his wife as a political maneuver to win back his standing with the new regime.

Peter Wiseman makes this case in his book The House of Augustus, where he argues that Augustus’s intentions to save the Republic were genuine, and that the Empire that followed was a consequence, not of his actions, but of subsequent rulers.